From Cutoffs to Pinstripes

It began with one cherry tomato and quickly escalated into a full-scale food fight. As an assortment of left-overs splattered about the room, you could feel the Chief Executive’s temperature rising. Minutes passed before he could get everyone’s attention. Fear suddenly gripped the participants, and the room settled to a hush. Revealing no emotion whatsoever, he exclaimed: “Nolan would be proud.” The Chief Executive smiled. Then the food fight resumed.

Ray Kassar, Atari’s Chief Executive Officer and chairman of the board, was referring to Nolan Bushnell, his predecessor. There is no small irony here since Bushnell not only founded Atari 10 years ago, but was the primary architect of Atari’s legendary, unorthodox workstyle that Kassar has tried so hard to change in the past three years. Working at Atari used to be like one continuous food fight, many former employees say; laboring there now, these people would have you believe, is about as lively as a visit to the county morgue.

Explains Gene Lipkin, the caustic former president of the coin-operated games division: “They do nice letters, and they answer their mail, and everybody is there at eight o’clock. I mean, they have the market on pinstriped suits today. There are more pinstriped suits walking around Atari then there are on the rest of this planet.”

Bob Brown, an ex-engineering supervisor who started with the company back in 1974, describes his thoughts after a recent visit to Atari: “Ray and everybody looked stoic and conservative, very three-piece suitish. So many people have come and gone that there was hardly anybody I knew anymore.”

Then what explained Kassar’s animated behavior as he presided over the executive’s food fight? “I think a lot of people misunderstand him” says Don Osborne, the current vice-president for marketing in the coin-op division. “I don’t think anybody has any idea what it’s like to be the chairman of the board of Atari. I don’t think anybody can comprehend the tremendous demand that is. This company is exploring uncharted territory. No company has ever grown this fast. There are no textbooks that can tell us what to do, and so we are really blazing the way. That’s a very unusual experience.”

To which Lipkin, Osborne’s former boss, replies: “They inherited a rocket and they’re all hanging on for dear life.”

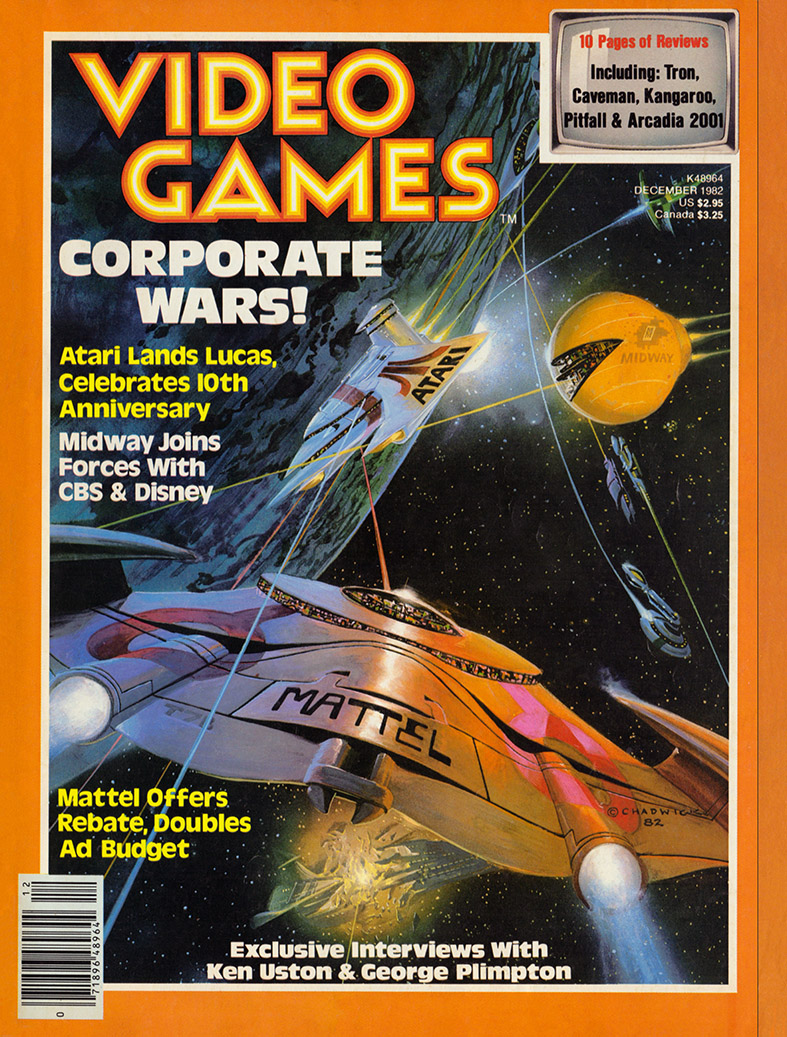

At a time when America’s industrial giants of the past like General Motors and U.S. Steel are crying the recession blues, that rocket keeps hurtling along at a record clip. Atari’s stats tell the story: Each of the last four years the company has doubled its revenues—from $165 million in 1979 to a projected $2 billion figure this year. Atari now accounts for approximately two-thirds of its parent company, Warner Communications Inc.’s total profits.

Ten years ago, Atari was a garage-shop operation that attracted some of the best and the brightest talent in California’s high-tech corridor of commerce, Silicon Valley. They wore blue jeans and sneakers and smoked pot and drank kegs full of beer while creating an industry no one thought was possible. Many of these people feel that they shared a unique moment in time during those early years and that Atari has changed drastically since they have left. That, of course, is to be expected of former employees. But these ex-Atarians do have some interesting stories to tell.

In the six years that have passed since Warner took the floundering video game company off Bushnell’s hands for a mere $32 million, much has transpired. The one thing though that all can agree upon is that Warner’s gamble has paid off. “I think you can say that Atari was the buy of the century,” says Brown. “I don’t know of any other better deal than that.”

The Saga Begins

Bob Brown was introduced to the grandaddy of all video games, Spacewar, in 1969, several years after Nolan Bushnell had started playing it at the University of Utah. Brown was fascinated by what he saw: a ballet of white figures dancing across the stage of a CRT screen. But he had no idea what to do with it. “How do you sell a $20,000 game system?” Brown wondered. “It just didn’t make sense to me that there was a market for games. Nolan showed there was. It was one of his wild visions.”

Just about that time the price of integrated circuits began to plummet. Bushnell, by now, had moved to California, taken a job in Ampex’s advanced technology division and, in his spare time, had started designing a system that could accommodate Spacewar. Dubbed Computer Space, he sold the prototype to Bill Nutting Associates, a relatively unknown arcade games manufacturer. Since few people had ever seen a video game before, marketing Computer Space was tough.

“We blew the whole coin-op industry’s mind,” Nutting recalls. “We built 1,500 and had to sell some by force. At the ‘71 A.M.O.A. (Amusement & Music Operators Association) show there was a few attempts to copy us. Then, the next year Nolan started Atari and came out with Pong. The business simply exploded.”

What Nutting fails to mention is the fact that he and Bushnell had had a falling out over Pong. Bushnell, who was chief engineer at Nutting then, wanted a bigger piece of the action for Pong. Nutting refused. “I didn’t like his deal,” he says. “The kind of royalties Nolan was asking didn’t seem fair to me. But, as they say, hindsight is 20-20.”

Out of a job, Bushnell reminded Ted Dabney, a former Ampex colleague, that they had once planned on starting a company some day. With the $500 in royalties Bushnell earned from Computer Space, they founded Syzygy. However, when they were informed by the Office of the Secretary of State that they were not the only would-be entrepreneurs fascinated by this celestial image (the moon, sun and earth in a straight line), Bushnell and Dabney rechristened the company Atari—after the check move in the Oriental game Go.

What’s in a name? In this case, plenty. If Syzygy foretold Atari’s present three-division corporate alignment of coin-operated games, consumer electronics and personal computers, Atari was an even brasher prognostication. As Bushnell likes to say, Atari is a polite warning to your competition that it is about to be engulfed.

The Stories of Pong

Almost five months to the day of Atari’s incorporation—June 27, 1972—Pong was unveiled at the annual trade gathering in Chicago. Like so many of Atari’s products to come, the work on Pong was a team effort in which only one member of the team received credit. In this case, it was Bushnell. Yet “King Pong,” as he was quickly dubbed by the press, readily admits to this fraud, joking: “I get the credit because I have more access to the press.”

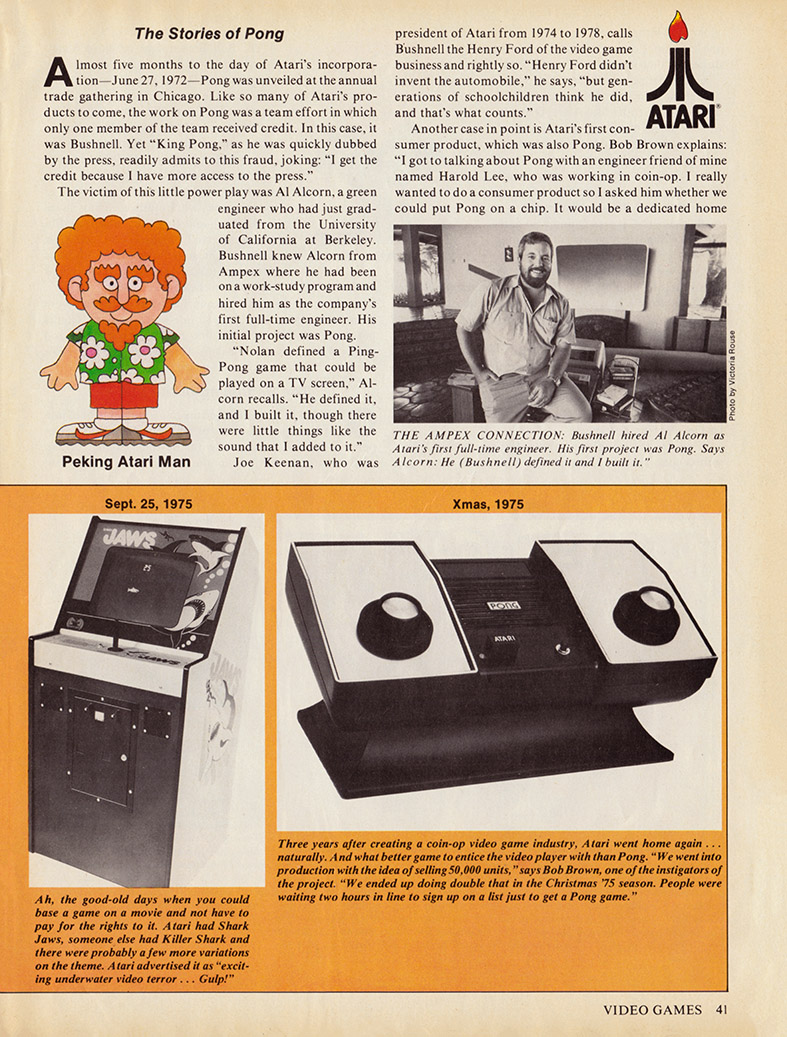

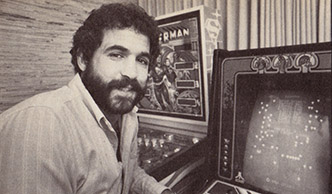

The victim of this little power play was Al Alcorn, a green engineer who had just graduated from the University of California at Berkeley. Bushnell knew Alcorn from Ampex where he had been on a work-study program and hired him as the company’s first full-time engineer. His initial project was Pong.

“Nolan defined a Ping-Pong game that could be played on a TV screen,” Alcorn recalls. “He defined it, and I built it, though there were little things like the sound that I added to it.”

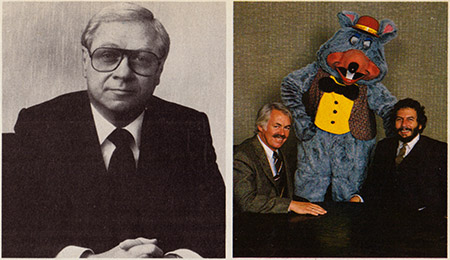

Joe Keenan, who was president of Atari from 1974 to 1978, calls Bushnell the Henry Ford of the video game business and rightly so. “Henry Ford didn’t invent the automobile,” he says, “but generations of schoolchildren think he did, and that’s what counts.”

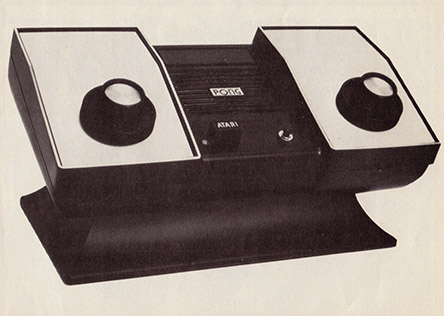

Another case in point is Atari’s first consumer product, which was also Pong. Bob Brown explains: “I got to talking about Pong with an engineer friend of mine named Harold Lee, who was working in coin-op. I really wanted to do a consumer product so I asked him whether we could put Pong on a chip. It would be a dedicated home game for TV that would essentially be like the coin-op Pong. He said it could be done, and then we sold Atari on the idea.”

Consumer sales and marketing was an entirely new direction for a company with deep coin-op roots like Atari. Distribution would be the key, and Atari didn’t have any on the retail level. Atari needed help and found it in the form of Sears Roebuck & Co. Barely. “A guy named Tom Quinn was the one who made the decision,” says Brown. “To me he was really the hero.” It was Quinn who gambled on Pong when he was, of all things, the sporting goods buyer.

“We went into production with the idea of selling 50,000 units.” Brown continues. “We ended up doing double that in the Christmas ‘75 season. People were waiting two hours in line to sign up on a list just to get a Pong game.”

What was interesting about the Sears-Atari alliance was how graphically it illustrated the chasm that existed between those who toiled in California’s positively laid-back Silicon Valley and the rest of the business world. Al Alcorn, who negotiated the Sears deal along with Gene Lipkin, recalls two incidents in particular.

“Some of the technicians who did our early chip layouts were a little spacey,” Alcorn says. “When the Sears guys came by we’d hide them in the back room. Well, Bob Brown had designed Video Music, our weirdest product ever. Hook it up to your stereo and TV at the same time, and the sound triggered some pretty psychedelic visuals. The Sears guys took one look and asked what we’d been smoking when we did that. Naturally, one of our techs lit up a joint and showed them.

“Another time, 10 guys came out to see our new plant in Los Gatos. We were in our everyday work clothes—tennis shoes and jeans—and they were all dressed in three-piecers. Everybody was getting a little uptight, so Nolan and a bunch of us jumped into some empty boxes and took

a ride around the building on the conveyer belt.

“That night the whole group had dinner. We all went home, cleaned up and changed into suits, hoping to make peace. Meanwhile, they’d gone back to their hotel and changed into jeans and sneakers. What a mix-up! The whole thing was pretty funny, we thought.”

The Beginning of the End

Gene Lipkin left Allied Leisure in Florida in 1974 to join Atari as vice-president for marketing. He still remembers his first conversations with Bushnell well. “Nolan really wanted to shoot the moon. ‘Listen guys,’ he’d say, ‘we can have this business the way it is, and it will be good to us for the rest of our lives, or we can take a big risk and go for it and see what happens, and we can blow it.’”

Bushnell went for the moon—selling seasonal consumer products—and blew it. Even with the success of dedicated Pong in ‘75, the cash wasn’t there—it was all going back into inventory that wouldn’t be sold off until Christmas. And coin-op games, by the way, weren’t exactly tearing up the arcades. Atari was in trouble.

Some have speculated over the years that Bushnell’s idiosyncratic style had finally caught up with him. To the contrary, Lipkin claims that Atari was a “well-run company” with good financial discipline. “We were not great structure guys,” he admits, “but we didn’t think you needed a great structure. We didn’t believe in a lot of things big companies were about. And, in fact, neither did Warner at that point.” The only thing Atari was lacking, he says, was money.

“It’s funny,” Lipkin goes on, “we had originally made a grocery list of 10 companies we would be willing to merge Atari with and Warner was not on that list. But through a connection, we made contact with Warner. We were really impressed with them, and I think they liked what they saw. Then boom-boom, the deal was made. I mean, it was that quick.” So well did everyone get along at first that Bushnell and Manny Gerard, Warner’s principal, exchanged signed notes on napkins in the restaurant where the deal transpired.

That was October ‘76. The next big news out of the Atari camp was another consumer product. This one carried the imposing namesake, Video Computer System (aka, VCS). It was Atari’s entry in the programmable game systems race. Code-named Stella, the VCS was conceptualized at Atari’s Grass Valley think tank, primarily by Steve Meyer (he is presently the acting president of the computer division), and then developed back at the Los Gatos headquarters by a group of engineers led by Jay Minor.

After its debut at the summer Consumer Electronics Show in 1977, Atari began mass producing the system in preparation for the expected Christmas rush. But sales were soft and stayed that way throughout the following year as the public continued to ignore this new and improved video game product. “It was an education problem,” contends Al Miller, who wrote several early cartridges before moving onto Activision. “People didn’t know whether to spend $30 to $50 on the numerous dedicated games that were still on the shelves or slap down $180 for the VCS, a considerably larger expense. But as the library of games began to diversify, the public came around. It was an evolutionary process.”

The Showdown

With Warner’s money, Atari built 800,000 Video Computer Systems in 1978. Ray Kassar, a former executive vice-president at Burlington Industries, had been installed as the president of the consumer division at the beginning of the year. All was not going well.

“It was a very bad year for the company,” explains Joe Keenan, who was president at the time. “Clearly we built too many units, which translated into potential disaster. We’re talking $40 million worth of inventory that the company was stuck with.”

Translated: Gerard’s superiors were growing more nervous by the day. According to Keenan, Gerard was being pressured to make a change. “I think he had the same confidence we had—that, hey, the 400,000 left-over units were going to move out, that ‘79 was going to be a banner year—but I think his job was as much on the line as ours turned out to be. I was in the meeting and sensed that the other fellows in the office of the president were very afraid of the Atari situation.”

The meeting—Warner’s annual budget meeting—took place in November. It proved to be Bushnell’s downfall. Before a crowd of high-level executives, Bushnell and Gerard locked horns, screaming at each other for hours. Says Keenan: “We were heads of a big, growing company, but we couldn’t make a major decision without calling Manny Gerard. He was the boss figure. Yet we didn’t want to get thrown out—we had a big financial stake there.”

But out they went (actually Bushnell was demoted from chairman to a director, and Keenan vacated the presidency for the chair position) and in came Kassar. “Ray could have been the scapegoat,” Keenan reflects bitterly, “but that wasn’t as satisfactory. Manny said he wanted to make him chief executive, and so c’est la vie.”

The Transition

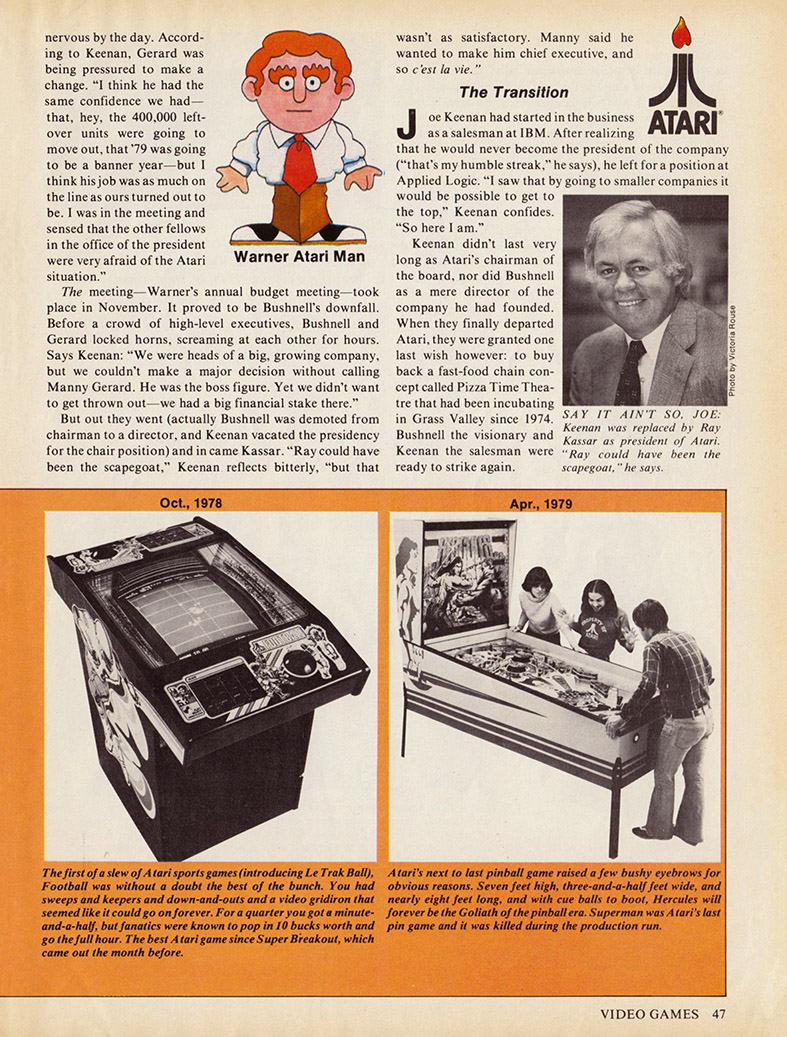

Joe Keenan had started in the business as a salesman at IBM. After realizing that he would never become the president of the company (“that’s my humble streak,” he says), he left for a position at Applied Logic. “I saw that by going to smaller companies it would be possible to get to the top,” Keenan confides. “So here I am.”

Keenan didn’t last very long as Atari’s chairman of the board, nor did Bushnell as a mere director of the company he had founded. When they finally departed Atari, they were granted one last wish however: to buy back a fast-food chain concept called Pizza Time Theatre that had been incubating in Grass Valley since 1974. Bushnell the visionary and Keenan the salesman were ready to strike again.

Meanwhile, over at Atari, the axe had begun to fall. Kassar’s first policy edict in January ‘79 was a freeze on all VCS software development. Essentially, this freed Bob Brown’s research and development division from its duties, making the entire staff of 30 engineers expendable. Brown’s divison was the first to go.

“I really had no conception that he was going to do that,” says the feisty engineer. “In fact, when Al (Alcorn) told me what had happened I didn’t understand what he was saying—I couldn’t conceive of Atari cutting off its future by chopping off its R & D work. It will always be my opinion that being engineering-oriented was what made Atari successful.”

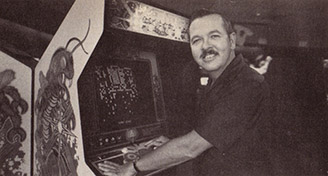

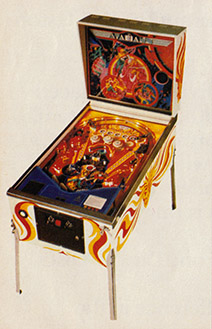

Later in the year, Gene Lipkin, the president of the entire coin-operated division, was forced to close down the company’s beleaguered pinball works. “It was a mess,” he admits, “but we pulled the plug too soon.” Noah Anglin, the engineering vice-president at the time, agrees. “Atari pinball machines were disasters, but they were also artistic masterpieces. I mean, we worked day and night, seven days a week on Superman, which was the state of the art, and then it got killed. That’s probably something I never really forgave the corporation for.”

But Kassar could care less—he was moving full-speed ahead. The new CEO concentrated mostly on selling the VCS year-round and establishing a company workstyle more consistent with his own. Kassar never had to send out a memo detailing work hours, a dress code and so on. Gradually, people got the message.

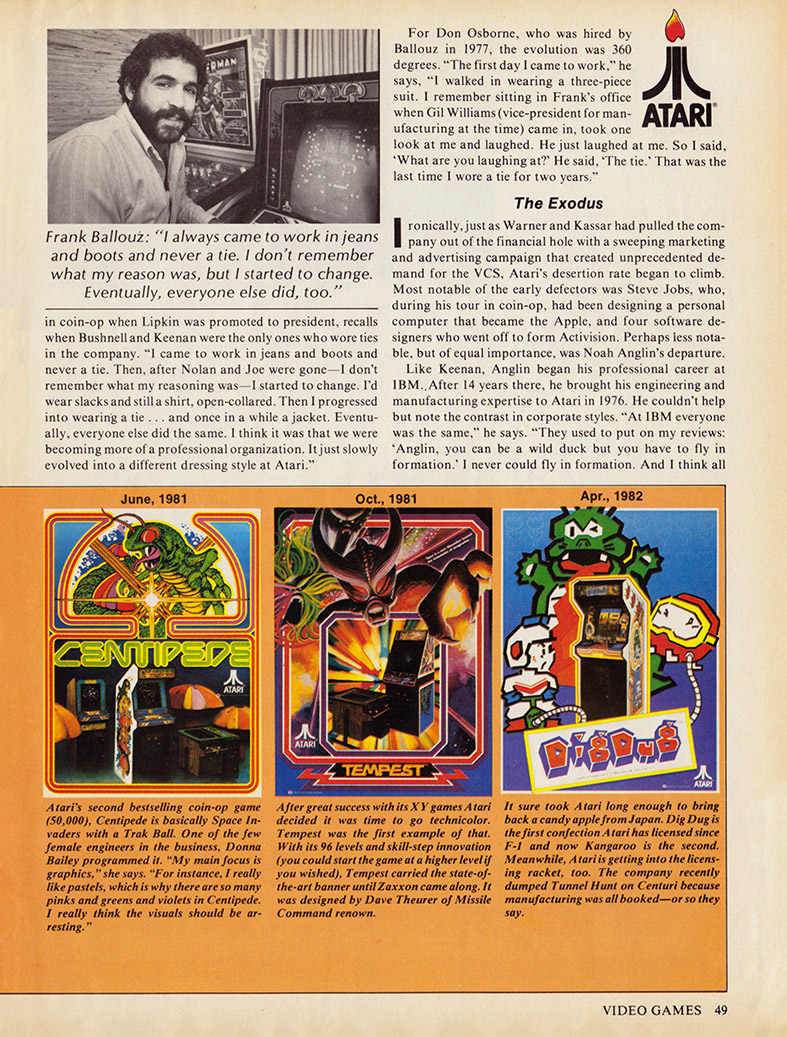

Frank Ballouz, who became vice-president for marketing in coin-op when Lipkin was promoted to president, recalls when Bushnell and Keenan were the only ones who wore ties in the company. “I came to work in jeans and boots and never a tie. Then, after Nolan and Joe were gone—I don’t remember what my reasoning was—I started to change. I’d wear slacks and still a shirt, open-collared. Then I progressed into wearing a tie…and once in a while a jacket. Eventually, everyone else did the same. I think it was that we were becoming more of a professional organization. It just slowly evolved into a different dressing style at Atari.”

For Don Osborne, who was hired by Ballouz in 1977, the evolution was 360 degrees. “The first day I came to work,” he says, “I walked in wearing a three-piece suit. I remember sitting in Frank’s office when Gil Williams (vice-president for manufacturing at the time) came in, took one look at me and laughed. He just laughed at me. So I said, ‘What are you laughing at?’ He said, ‘The tie.’ That was the last time I wore a tie for two years.”

The Exodus

Ironically, just as Warner and Kassar had pulled the company out of the financial hole with a sweeping marketing and advertising campaign that created unprecedented demand for the VCS, Atari’s desertion rate began to climb. Most notable of the early defectors was Steve Jobs, who, during his tour in coin-op, had been designing a personal computer that became the Apple, and four software designers who went off to form Activision. Perhaps less notable, but of equal importance, was Noah Anglin’s departure.

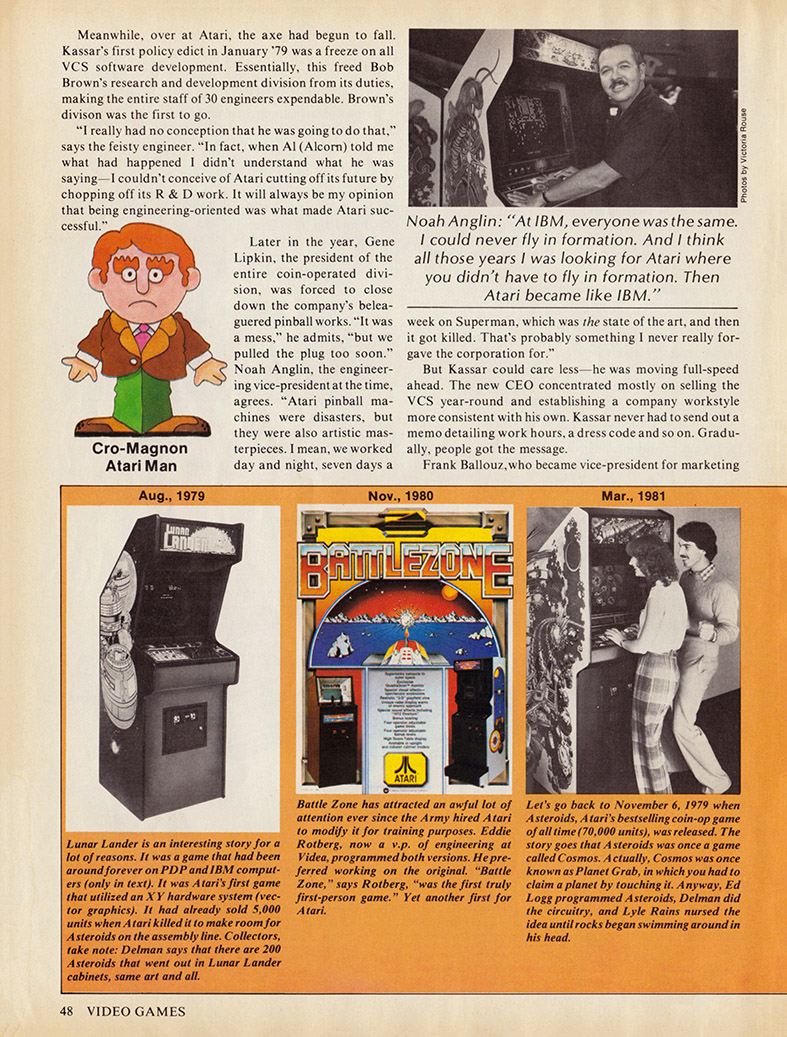

Like Keenan, Anglin began his professional career at IBM .. After 14 years there, he brought his engineering and manufacturing expertise to Atari in 1976. He couldn’t help but note the contrast in corporate styles. “At IBM everyone was the same,” he says. “They used to put on my reviews: ‘Anglin, you can be a wild duck but you have to fly in formation.’ I never could fly in formation. And I think all those years I was looking for Atari where you didn’t have to fly in formation.”

But times change, and Anglin grew unhappy at Atari as well. As an engineer, he was particularly disturbed by the slow movement of product out the door. “The company just got too big, too fast,” he maintains. “Three months was not an unusual length of time to develop and manufacture a game when I got there. Suddenly, it was taking a year, a year and a half.

“We might yell and scream for 15 minutes at each other,” Anglin adds, “but we’d make a decision that most companies would take a year to make. We were making decisions on the fly

that involved major changes in the company. They can’t do that anymore. Atari became like IBM.”

Indeed, the company’s growth has been dramatic: from less than 1,000 employees about the time of the Warner sale to nearly 10,000 today. So massive has Atari become—the company has more than 50 office buildings in Silicon Valley 50 miles south of San Francisco and manufacturing facilities in El Paso, Tex., Taiwan and Ireland—that few really know who’s making what decisions on the executive level. Many observers claim that Atari is now “out of touch, out of mind.”

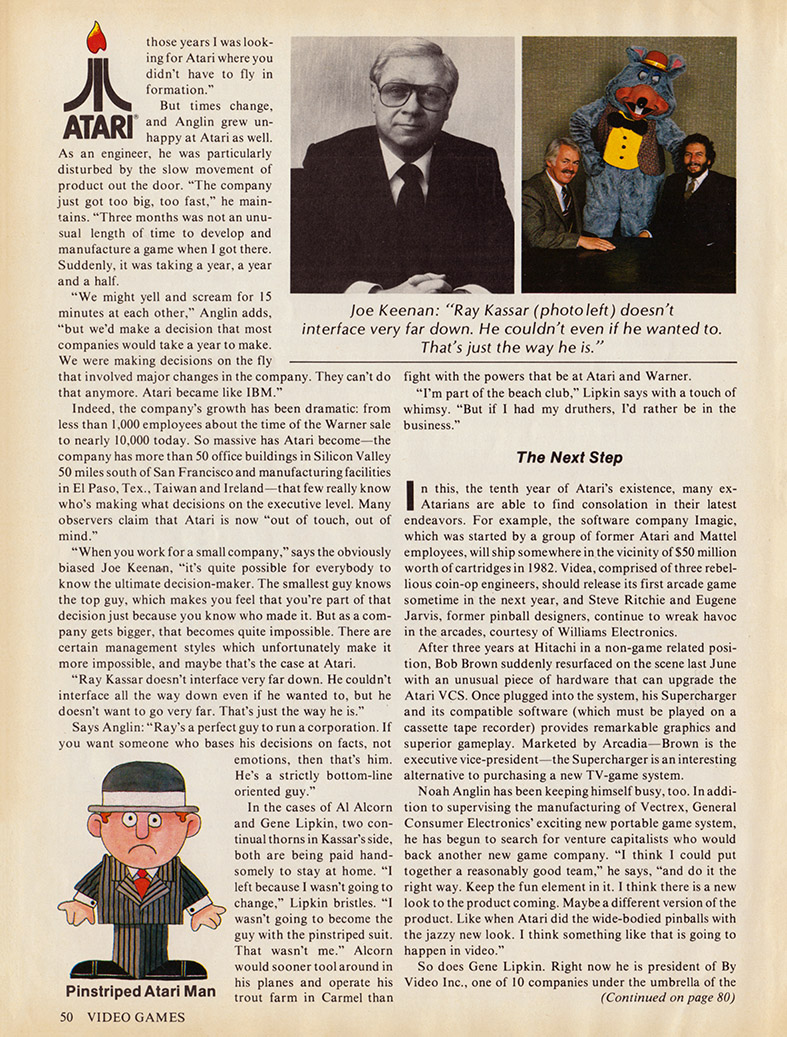

“When you work for a small company,” says the obviously biased Joe Keenan, “it’s quite possible for everybody to know the ultimate decision-maker. The smallest guy knows the top guy, which makes you feel that you’re part of that decision just because you know who made it. But as a company gets bigger, that becomes quite impossible. There are certain management styles which unfortunately make it more impossible, and maybe that’s the case at Atari.

“Ray Kassar doesn’t interface very far down. He couldn’t interface all the way down even if he wanted to, but he doesn’t want to go very far. That’s just the way he is.” Says Anglin: “Ray’s a perfect guy to run a corporation. If you want someone who bases his decisions on facts, not emotions, then that’s him. He’s a strictly bottom-line oriented guy.”

In the cases of Al Alcorn and Gene Lipkin, two continual thorns in Kassar’s side, both are being paid handsomely to stay at home. “I left because I wasn’t going to change,” Lipkin bristles. “I wasn’t going to become the guy with the pinstriped suit. That wasn’t me.” Alcorn would sooner tool around in his planes and operate his trout farm in Carmel than fight with the powers that be at Atari and Warner.

“I’m part of the beach club,” Lipkin says with a touch of whimsy. “But if I had my druthers, I’d rather be in the business.”

The Next Step

In this, the tenth year of Atari’s existence, many ex-Atarians are able to find consolation in their latest endeavors. For example, the software company Imagic, which was started by a group of former Atari and Mattel employees, will ship somewhere in the vicinity of $50 million worth of cartridges in 1982. Videa, comprised of three rebellious coin-op engineers, should release its first arcade game sometime in the next year, and Steve Ritchie and Eugene Jarvis, former pinball designers, continue to wreak havoc in the arcades, courtesy of Williams Electronics.

After three years at Hitachi in a non-game related position, Bob Brown suddenly resurfaced on the scene last June with an unusual piece of hardware that can upgrade the Atari VCS. Once plugged into the system, his Supercharger and its compatible software (which must be played on a cassette tape recorder) provides remarkable graphics and superior gameplay. Marketed by Arcadia—Brown is the executive vice-president—the Supercharger is an interesting alternative to purchasing a new TV-game system.

Noah Anglin has been keeping himself busy, too. In addition to supervising the manufacturing of Vectrex, General Consumer Electronics’ exciting new portable game system, he has begun to search for venture capitalists who would back another new game company. “I think I could put together a reasonably good team,” he says, “and do it the right way. Keep the fun element in it. I think there is a new look to the product coming. Maybe a different version of the product. Like when Atari did the wide-bodied pinballs with the jazzy new look. I think something like that is going to happen in video.”

So does Gene Lipkin. Right now he is president of By Video Inc., one of 10 companies under the umbrella of the Catalyst Group, Bushnell’s assembly line for would-be entrepreneurs. “We see the business as a real business of opportunity,” Lipkin explains. “Clearly a business that we can make. a big contribution to, because we think the technology movement in the business has slowed down significantly in terms of where people are willing to take risks. They’re not doing that today. The big corporate mentality of ‘Don’t rock the boat’ has become very widespread in the Valley. Well, I don’t believe that that’s how great companies get started or really grow.

“Atari was an incredible, incredible story,” Lipkin goes on. “And a real credit to the fact that entrepreneurs can succeed, and a credit to hard work. Success comes to those who hustle wisely. I think that Atari really demonstrated that.”

The wisest hustlers of them all—at least in this saga—were Nolan Bushnell and Joe Keenan. Rewarded generously by Warner in 1976 (Bushnell cleared $15 million, Keenan $2.2), the duo, as mentioned earlier, immediately turned around and bought the one operating Pizza Time Theatre and the concept for a half-million dollars. Four years later, more than 100 such stores have been opened, and revenues are approaching $75 million. Although Pizza Time’s success is similar in many ways to Atari’s early growth, Keenan cites what he considers the major differences. “Nolan and I are 10 years older, and therefore our henchmen are 10 years older than they would have been at Atari. There is definitely a difference in how you behave when you’re 28 and how you behave when you’re 38. So, this company is a little calmer, a little more mature than Atari was, but not a lot.”

Keenan, however, is still mischievous enough to take a last shot at Atari. “I’m proud of the fact that already four years after we left they’re still growing on absolutely the same products that we put into position. Their big success story has been the VCS—well, that was our concept. We engineered it, we built it, we brought it into the market. I’m actually disappointed that Atari hasn’t innovated a thing since we left. If that doesn’t change, Atari is going to lose its commanding position, and I might be embarrassed by having been associated with it.”

Atari needn’t worry for now. It’s not about to lose its commanding position in the video games business, especially with George Lucas (Lucasfilm and Atari have agreed on a joint game venture) and McDonald’s (“Taste the thrill of Atari at McDonald’s”) on the company’s side.

But there is talk in the Valley about the expiration of Bushnell’s non-compete agreement with Atari. Talk may be cheap, but one of Bushnell’s confidants, asked recently if “King Pong” has been considering a return to the video game arena, responded firmly: “On October 1, 1983 at 10 a.m. Nolan will have a game on the street.”

Timeline

Timeline (Research Version)

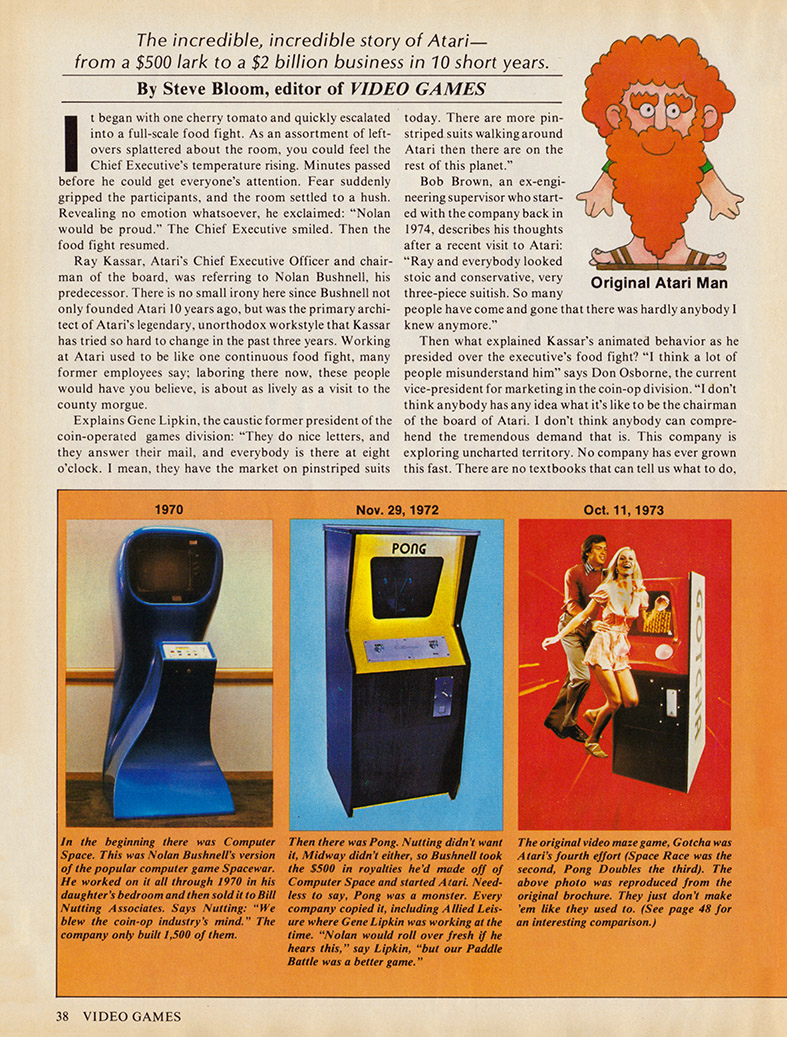

1970

In the beginning there was Computer Space. This was Nolan Bushnell’s version of the popular computer game Spacewar. He worked on it all through 1970 in his daughter’s bedroom and then sold it to Bill Nutting Associates. Says Nutting: “We blew the coin-op industry’s mind.” The company only built 1,500 of them.

Nov. 29, 1972

Then there was Pong. Nutting didn’t want it, Midway didn’t either, so Bushnell took the $500 in royalties he’d made off of Computer Space and started Atari. Needless to say, Pong was a monster. Every company copied it, including Allied Leisure where Gene Lipkin was working at the time. “Nolan would roll over fresh if he hears this,” say Lipkin, “but our Paddle Battle was a better game.”

Oct. 11, 1973

The original video maze game, Gotcha was Atari’s fourth effort (Space Race was the second, Pong Doubles the third). The above photo was reproduced from the original brochure. They just don’t make ’em like they used to. (See page 48 for an interesting comparison.)

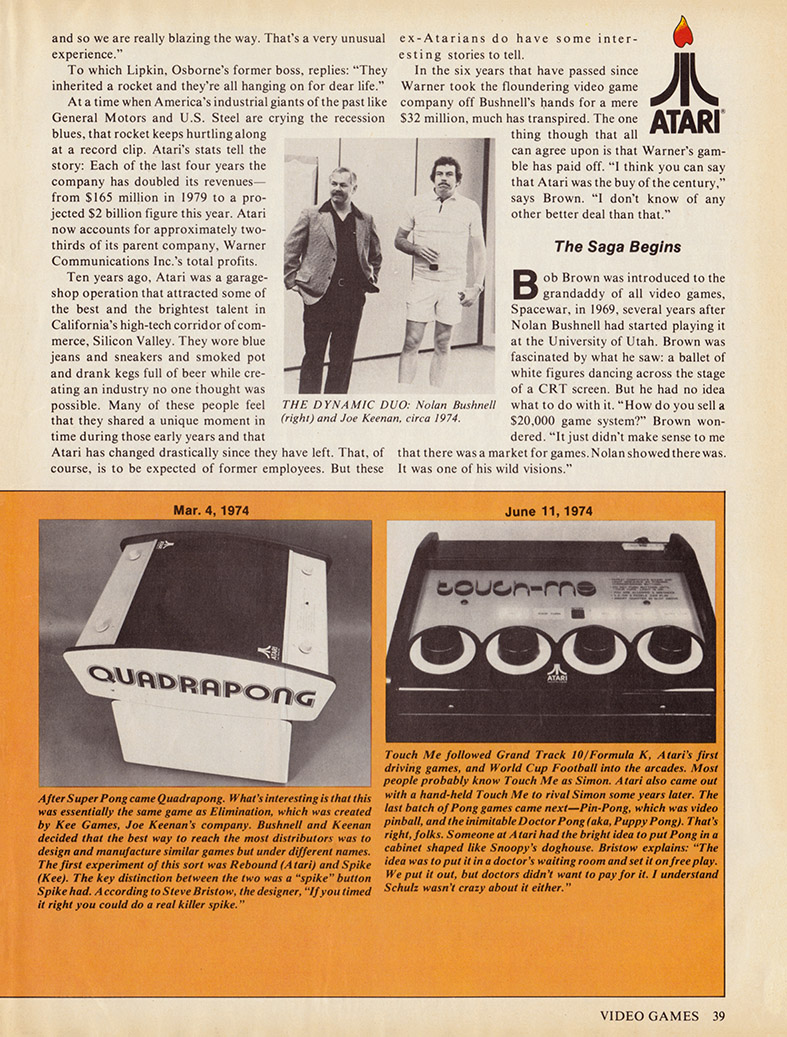

Mar. 4, 1974

After Super Pong came Quadrapong. What’s interesting is that this was essentially the same game as Elimination, which was created by Kee Games, Joe Keenan’s company. Bushnell and Keenan decided that the best way to reach the most distributors was to design and manufacture similar games but under different names. The first experiment of this sort was Rebound (Atari) and Spike (Kee). The key distinction between the two was a “spike” button Spike had. According to Steve Bristow, the designer, “If you timed it right you could do a real killer spike.”

June 11, 1974

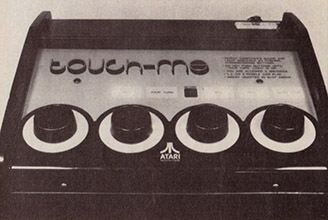

Touch Me followed Grand Track 10/Formula K, Atari’s first driving games, and World Cup Football into the arcades. Most people probably know Touch Me as Simon. Atari also came out with a hand-held Touch Me to rival Simon some years later. The last batch of Pong games came next—Pin-Pong, which was video pinball, and the inimitable Doctor Pong (aka, Puppy Pong). That’s right, folks. Someone at Atari had the bright idea to put Pong in a cabinet shaped like Snoopy’s doghouse. Bristow explains: “The idea was to put it in a doctor’s waiting room and set it on free play. We put it out, but doctors didn’t want to pay for it. I understand Schulz wasn’t crazy about it either.”

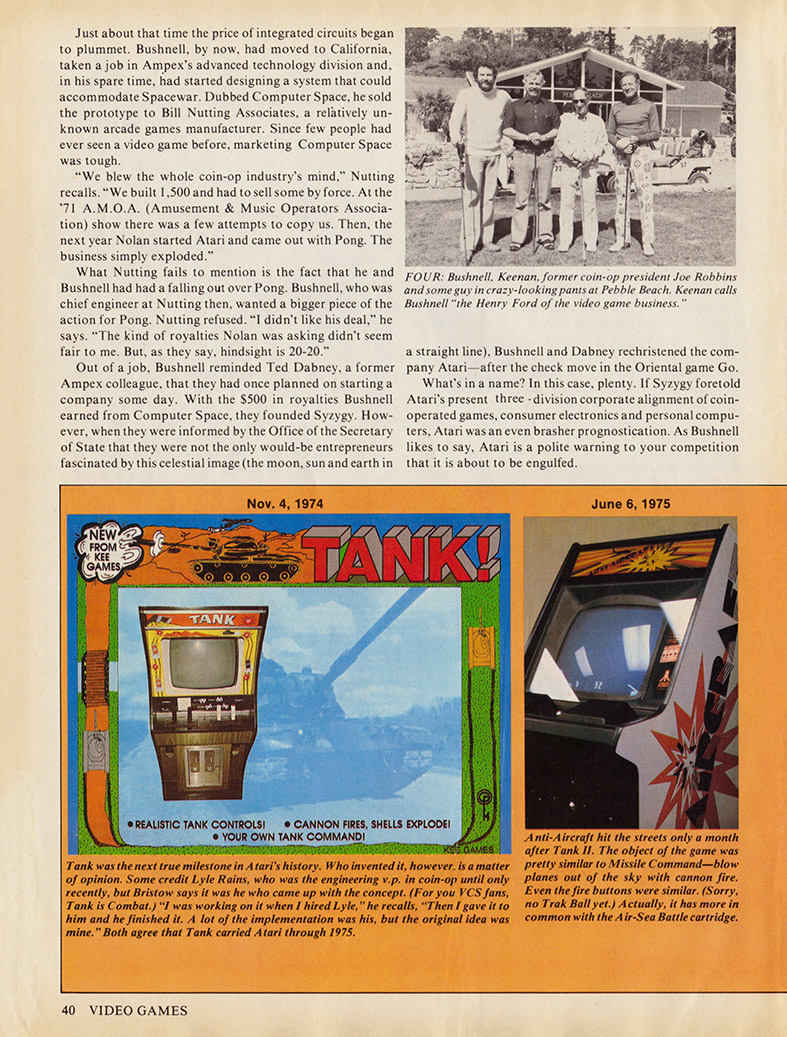

Nov. 4, 1974

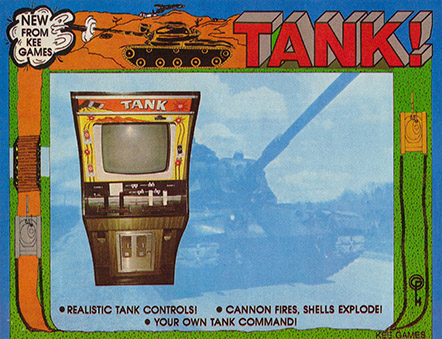

Tank was the next true milestone in Atari’s history. Who invented it, however, is a matter of opinion. Some credit Lyle Rains, who was the engineering v.p. in coin-op until only recently, but Bristow says it was he who came up with the concept. (For you VCS fans, Tank is Combat.) “I was working on it when I hired Lyle,” he recalls, “Then I gave it to him and he finished it. A lot of the implementation was his, but the original idea was mine.” Both agree that Tank carried Atari through 1975.

June 6, 1975

Anti-Aircraft hit the streets only a month after Tank II. The object of the game was pretty similar to Missile Command—blow planes out of the sky with cannon fire. Even the fire buttons were similar. (Sorry, no Trak Ball yet.) Actually, it has more in common with the Air-Sea Battle cartridge.

Sept. 25, 1975

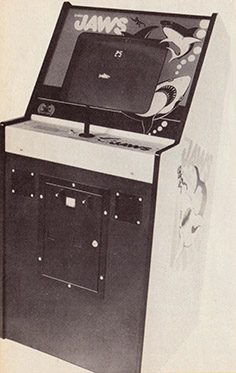

Ah, the good-old days when you could base a game on a movie and not have to pay for the rights to it. Atari had Shark Jaws, someone else had Killer Shark and there were probably a few more variations on the theme. Atari advertised it as “exciting underwater video terror … Gulp!”

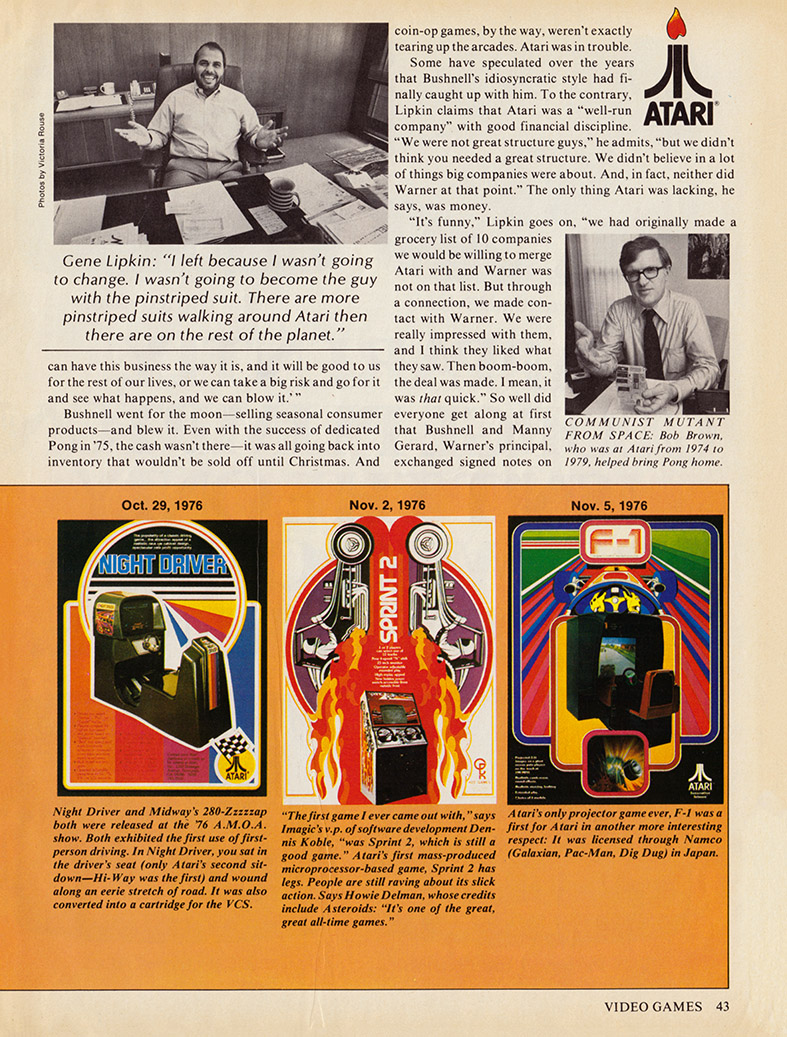

Xmas, 1975

Three years after creating a coin-op video game industry, Atari went home again … naturally. And what better game to entice the video player with than Pong. “We went into production with the idea of selling 50,000 units,” says Bob Brown, one of the instigators of the project. “We ended up doing double that in the Christmas ‘75 season. People were waiting two hours in line to sign up on a list just to get a Pong game.”

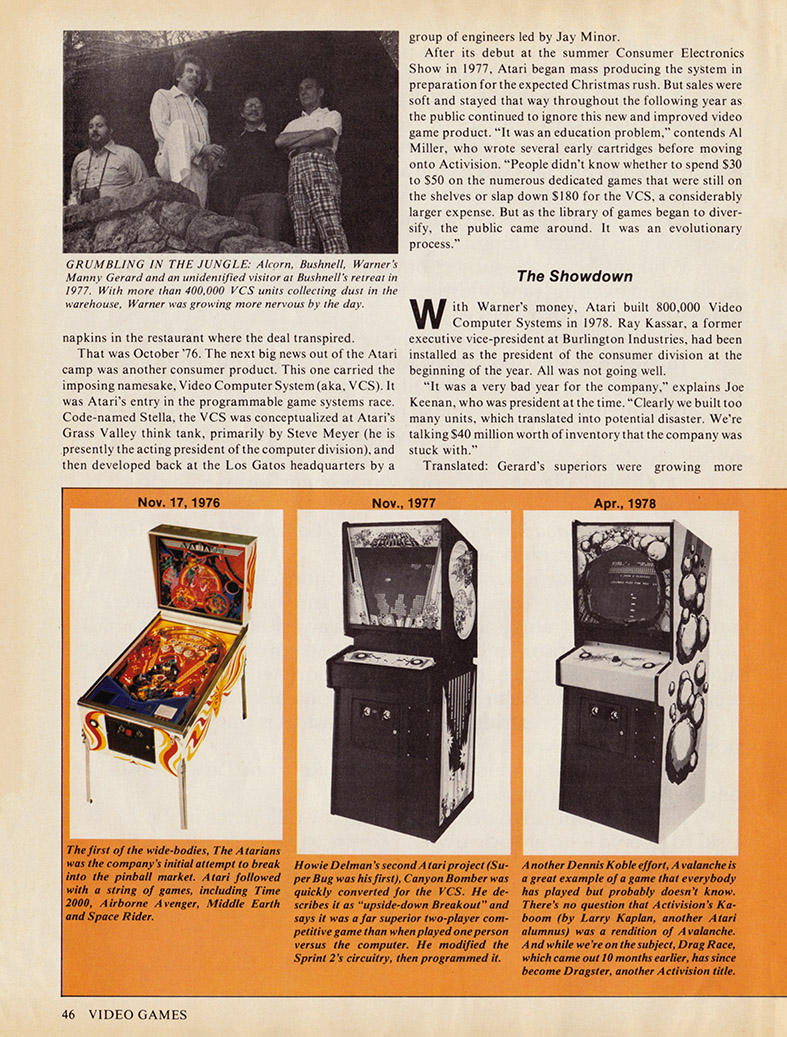

Apr. 13, 1976

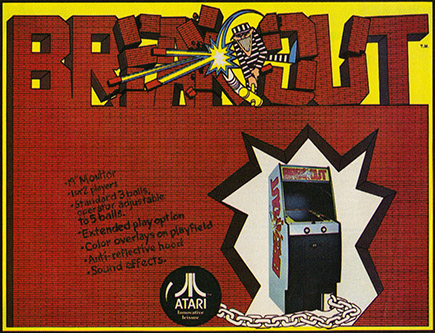

The ultimate in Pong, Breakout was designed by “this non-degreed engineer, but sharp kid from Palo AIto,” explains Bristow, “named Steve Jobs.” (Do you know him? He’s only the president of Apple Computer.) Jobs had an unusual working arrangement with Atari at the time. Bushnell would describe a game and specify a certain number of integrated circuits (ICs) he wanted Jobs to use. For every IC he saved he received a $100 bonus. Jobs turned out a very compact prototype of what turned into Breakout. “I think he brought it down from 80 to 30 ICs,” says Bristow. “It wasn’t common but that’s how that one happened.”

Aug. 4, 1976

One of Atari’s many driving games throughout its early years, Lemans featured 10 different tracks, each named after a famous raceway. Slow and clunky, Lemans was definitely not a milestone by any stretch of the imagination.

Oct. 29, 1976

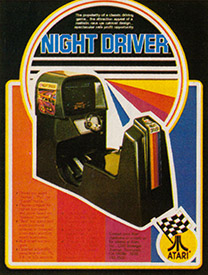

Night Driver and Midway’s 280-Zzzzzap both were released at the ‘76 A.M.O.A. show. Both exhibited the first use of first-person driving. In Night Driver, you sat in the driver’s seat (only Atari’s second sit-down—Hi-Way was the first) and wound along an eerie stretch of road. It was also converted into a cartridge for the VCS.

Nov. 2, 1976

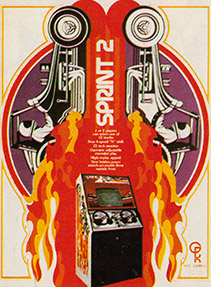

“The first game I ever came out with,” says Imagic’s v.p. of software development Dennis Koble, “was Sprint 2, which is still a good game.” Atari’s first mass-produced microprocessor-based game, Sprint 2 has legs. People are still raving about its slick action. Says Howie Delman, whose credits include Asteroids: “It’s one of the great, great all-time games.”

Nov. 5, 1976

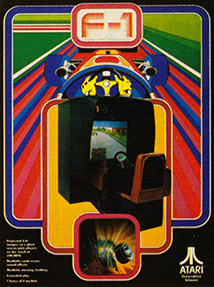

Atari’s only projector game ever, F-1 was a first for Atari in another more interesting respect: It was licensed through Namco (Galaxian, Pac-Man, Dig Dug) in Japan.

Nov. 17, 1976

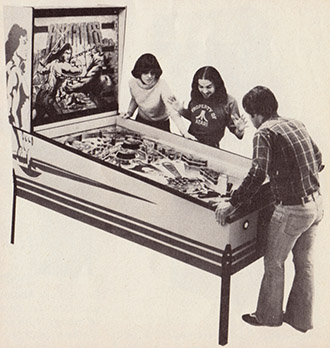

The first of the wide-bodies, The Atarians was the company’s initial attempt to break into the pinball market. Atari followed with a string of games, including Time 2000, Airborne Avenger, Middle Earth and Space Rider.

Nov., 1977

Howie Delman’s second Atari project (Super Bug was his first), Canyon Bomber was quickly converted for the VCS. He describes it as “upside-down Breakout” and says it was a far superior two-player competitive game than when played one person versus the computer. He modified the Sprint 2’s circuitry, then programmed it.

Apr., 1978

Another Dennis Koble effort, Avalanche is a great example of a game that everybody has played but probably doesn’t know. There’s no question that Activision’s Kaboom (by Larry Kaplan, another Atari alumnus) was a rendition of Avalanche. And while we’re on the subject, Drag Race, which came out 10 months earlier, has since become Dragster, another Activision title.

Oct., 1978

The first of a slew of Atari sports games (introducing Le Trak Ball), Football was without a doubt the best of the bunch. You had sweeps and keepers and down-and-outs and a video gridiron that seemed like it could go on forever. For a quarter you got a minute-and-a-half, but fanatics were known to pop in 10 bucks worth and go the full hour. The best Atari game since Super Breakout, which came out the month before.

Apr., 1979

Atari’s next to last pinball game raised a few bushy eyebrows for obvious reasons. Seven feel high, three-and-a-half feel wide, and nearly eight feet long, and with cue balls to boot, Hercules will forever be the Goliath of the pinball era. Superman was Atari’s last pin game and it was killed during the production run.

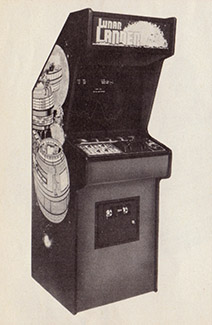

Aug., 1979

Lunar Lander is an interesting story for a lot of reasons. It was a game that had been around forever on PDP and IBM computers (only in text). It was Atari’s first game that utilized an XY hardware system (vector graphics). It had already sold 5,000 units when Atari killed it to make room for Asteroids on the assembly line. Collectors, take note: Delman says that there are 200 Asteroids that went out in Lunar Lander cabinets, same art and all.

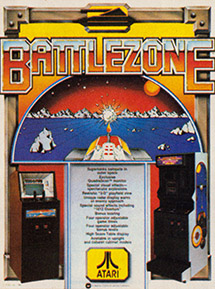

Nov., 1980

Battle Zone has attracted an awful lot of attention ever since the Army hired Atari to modify it for training purposes. Eddie Rotberg, now a v.p. of engineering at Videa, programmed both versions. He preferred working on the original. “Battle Zone,” says Rotberg, “was the first truly first-person game.” Yet another first for Atari.

Mar., 1981

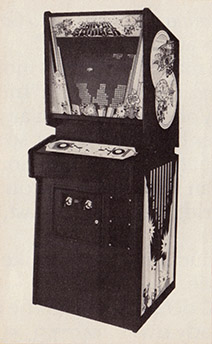

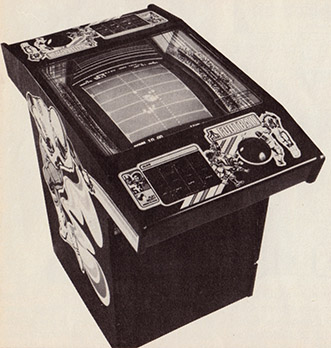

Let’s go back to November 6, 1979 when Asteroids, Atari’s bestselling coin-op game of all time (70,000 units), was released. The story goes that Asteroids was once a game called Cosmos. Actually, Cosmos was once known as Planet Grab, in which you had to claim a planet by touching it. Anyway, Ed Logg programmed Asteroids, Delman did the circuitry, and Lyle Rains nursed the idea until rocks began swimming around in his head. (Archivist Note: Asteroids Deluxe is pictured)

June, 1981

Atari’s second bestselling coin-op game (50,000), Centipede is basically Space Invaders with a Trak Ball. One of the few female engineers in the business, Donna Bailey programmed it. “My main focus is graphics,” she says. “For instance, I really like pastels, which is why there are so many pinks and greens and violets in Centipede. I really think the visuals should be arresting.”

Oct., 1981

After great success with its XY games Atari decided it was time to go technicolor. Tempest was the first example of that. With its 96 levels and skill-step innovation (you could start the game at a higher level if you wished), Tempest carried the state-of-the-art banner until Zaxxon came along. It was designed by Dave Theurer of Missile Command renown.

Apr., 1982

It sure took Atari long enough to bring back a candy apple from Japan. Dig Dug is the first confection Atari has licensed since F-1 and now Kangaroo is the second. Meanwhile, Atari is getting into the licensing racket, too. The company recently dumped Tunnel Hunt on Centuri because manufacturing was all booked—or so they say.

Source Pages