Book Beat

Notes from the Video Game Underground

The place to start, I suppose, is with the phone call that interrupted a good night’s sleep one morning last February. Two months earlier David Sklansky, a professional poker player living here in Las Vegas, and I had submitted a lengthy proposal to Prentice-Hall for a book called Expert Poker. We still hadn’t received a reply.

The phone call was from Peter Tobey, publisher of Banbury Books. He and editor Ed Claflin had read “Plugged into Electronic Games,” an article of mine which appeared in Games magazine a month earlier, and liked it.

“If we were to send you a couple of hundred video game cartridges, do you think you could write 300-to-400-word descriptions of them? The book we have in mind is A Buyer’s Guide to Home Video Games.”

Quickly, I realized this was the sort of call I had been waiting a lifetime for. “Yes,” I said, dreamily. “I think I can manage that.”

Tobey suggested a dollar figure as an advance. It was more than I’d received for anything I’d written in the past, and here he was offering it before I’d submitted a word. Gamblers, I could see, didn’t live only in Las Vegas. I accepted Tobey’s offer on the spot.

As might be expected, a response from Prentice-Hall was waiting in the mail the next day. “Dear Mr. Dionne and Mr. Sklansky: It is a pleasure to send you the contracts for your book. …” Suddenly, I was obliged to complete a video games book by Apr. 9 and a poker book by May 15. I really believed I could finish them both on schedule.

How did I get myself into such a fix? Let me back up a bit and try to explain. A couple of years earlier, as features editor of Gambling Times, I had discovered the fascination and pleasure of playing games for cash. I had always played games—from Parcheesi to Pong—but I’d never experienced the excitement of the gambling life until I took up backgammon and won a few small tourneys. Soon I learned to count and challenge Las Vegas casinos at blackjack, found a bookie and started betting sports, and became a regular in a Friday night poker game.

Ah, but then in the spring of 1981, along came Pac-Man, the most intoxicating game of all. Investing god knows how many quarters in that puckish yellow dot, I learned patterns, ate fruit, hit 50,000, 100,000. I got past the terrible ninth key. I reached 200,000 and still my appetite wasn’t sated. In his book Score! Beating the Top 16 Video Games, Ken Uston refers to a Las Vegas poker player who tests his concentration by playing several games of Pac-Man before heading to the casino for an evening at the tables, That player is me. (Uston actually wrote, “If he does well he goes out to play poker; if he does poorly, he goes home.”—Ed.)

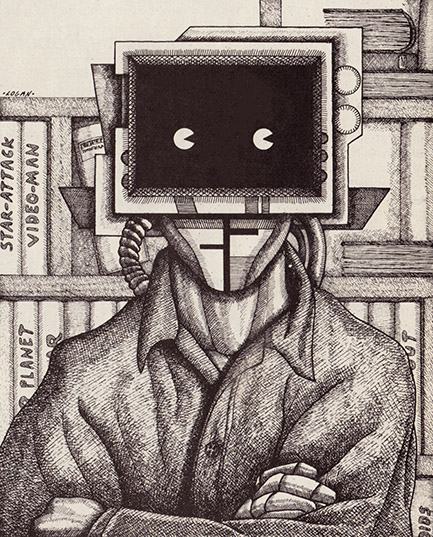

Which brings me back to the happy dilemma of having to write two books in a matter of three months. I moved the television set from the living room to my office, set up a large table in front of it, and went to work on the video book. My starry-eyed plan was to do ten games a day, spending 45 minutes playing and mastering each game and another 45 minutes writing it up—a 15-hour work day every day, including weekends. Silently, steadfastly, enclosed like a troll in my dungeon-office, I zapped aliens, scrambled through mazes, eluded dragons, took on computer blackjack dealers, tennis players and chess opponents, made notes—the black Angus in Stampede appears after you rope two Herefords; the ball in Breakout changes angles after the seventh hit—and wrote and wrote and wrote. Day and night, already ill-defined in Las Vegas, became a single, fuzzy blur. I worked all the time, ate only when I was hungry, slept only when I was tired.

After a few weeks I began to feel detached. Life was something for people out there beyond my television set and typewriter, for people who somehow had time to converse, laugh, date, go shopping, do the laundry. A simple stop at the mailbox became a kind of revelation: From there I could see people actually lying out by the pool and the jacuzzi, doing absolutely nothing but soaking up the sun, reading a novel, drinking a beer, talking to one another. How was it possible? It seemed like something I had known only in another incarnation.

My isolation from society drove me to the Tropicana, the Desert Inn, the Castaways, where I played poker. Residing in Las. Vegas was a big plus in this respect. In Hoboken or Topeka or even Los Angeles or New York, whom do you call at midnight? Where do you go besides the all-night diner at 4 a.m.? Ah, but in Las Vegas there is always a poker game.

Once I sat down at a full table of seven-card stud at the Castaways, I became lost in the game’s ebb and flow. I’d play for two hours, six hours, 10 hours. Poker provided me with everything my solitary, workaholic existence lacked—company, camaraderie, relaxation, ego gratification, instant reward and, sometimes, when I played badly, instant punishment.

There was something else, too. I’d been playing games all day that were locked inside the TV screen. They were distant. It’s true I was participating. Indeed, I was making things happen with my buttons and joysticks. Yet I was not of the game. There was always a surrogate taking my place out there on the screen so that I was as much a spectator as a player. On the other hand, poker was a real game. I was totally involved, a total part of the action, and—notwithstanding the luck factor—I was total master of my fate. There was something almost sensual about the feel of the cards when I received them and the chips as I stacked them, divided them, shuffled them and stacked them again. Most of all, there was the bright, exciting clash of my mind and my abilities against those of seven other human beings. These things, I now have the temerity to aver, no video game can provide.

Meanwhile, something was happening back in the electronic battle-zone of my office. I had expected that writing the book would be a chore to get done, a product to be uniformly manufactured—one game description popping out of my typewriter every hour and a half as regularly as Big Macs off a McDonald’s grill. For better or worse, that’s not the way it worked out. Some games, usually the worst of them, did take 45 minutes or less to digest, but any game worth its salt took considerably longer. It was usually easy enough to master the mechanics of games I’d never played, but learning to play them well was another matter. One simply does not master Atari’s Superman, Imagic’s Star Voyager or N.A.P.’s Great Wall Street Fortune Hunt in 45 minutes. One is lucky if he’s adept at them after two or three hours. What’s more, I was working under the decided disadvantage that so many of the games were fun to play. After I’d played Activision’s Freeway, N.A.P.’s K.C. Munchkin or Astrocade’s Galactic Invasion long enough to feel I could write a competent analysis of it, I found myself nevertheless playing it again and again and again, determined to better my high score, to overcome another hurdle and yet another and another. I persuaded myself I was doing further research, but mostly I was having fun.

Then there was the writing. Little 300-to-400-word descriptions. Nothing to them. Zip. Zip. Zip. But, no, that’s not the way it was. Somewhat to my surprise, the writing too became enormous fun, and when writing is fun—for me at least—it is time-consuming. With very few exceptions, each entry became a little essay, a literary five-finger exercise which I worked at lovingly, painstakingly, I’d even dare say artfully, I didn’t just write. I molded, revised, pared, polished, searched for le mot juste. At the same time, many of the descriptions grew to 600, 1,000 1,500 words and longer. N.A.P.’s Conquest of the World led to a brief treatise on games and social attitudes. Mattel’s Major League Baseball became a panegyric on the summer game. But mostly I simply fell in love with what I was doing.

“Great writing,” I told a barfly over drinks at the time, “can appear in a book on video games as surely as it can in a novel or a poem.”

He nodded in agreement like only a barfly could.

“There are passages in my book,” I asserted, “worthy of comparison to the first sentence of Pride and Prejudice.”

A gross exaggeration, I expect, that no doubt caused the Reverend Austin’s daughter to smile sardonically from her heavenly cloud. The point—well-taken or not—was this was just the kind of writing I was trying to produce. Hence, on a good day I was lucky to get through not 10 games but four or five. Inevitably, my Apr. 9 deadline had to be extended—first to May 1, then to May 15. At the same time, I obtained an extension for the poker book.

My monastic life continued through April and May. I wondered what it was like to have a drink with an attractive woman, to have dinner out, to have an evening of conversation with old friends over old wine. My world thickened into a soup of blips, bleeps, poker hands, TV dinners, words and more words, the rat-a-tat-tat of missile fire and the rat-a-tat-tat of typewriter keys. As the end approached, I learned of new games being released—Activision’s Chopper Command and Star Master, Atari’s Berzerk, Intellivision’s Star Strike, Parker Brothers’ Frogger and The Empire Strikes Back—all of which, of course, had to be included in the book. I also discovered an entire TV-game system, APF Electronics’ MP-1000, which I had overlooked when I started the project.

Finally, one morning in late May, to my utter amazement, there was nothing more to do. I crammed a 600-page manuscript covering more than 250 games into a box and Federal-Expressed it to Wayne, Pa. The book was finished.

For two days straight I played poker and won $285. Then, with David Sklansky, I plunged into the poker book. With 180 pages written, I interrupted that book to put together this article. It’s already July, and I’m still wondering when I’ll again be able to enjoy those amenities I had once known. Someday, hopefully, I’ll find out. Unless, of course, there’s a sensational new video game to play. Or a good poker game down at the Castaways.

Source Pages