The Making of Tron

Special Effects Leap Into The Future

Let’s pretend that the technology of moviemaking is really a spaceship. It “blasted off” in 1898 from the Menlo Park, New Jersey laboratory of Thomas Edison, who shot the first close-up (a guy by the name of Fred Ott sneezing at the camera) and the first movie with a story (The Great Train Robbery). By the late 1950s, special-effect technology was halfway to the moon: It was the era of Godzilla, Klaatu, and 3-D glasses. By 1977, the year George Lucas gave us Star Wars, movies had landed on the moon. But today we see the moon as our next-door neighbor in space. There are more distant worlds for us to explore.

Now—five years later—American movies are hurtling past Mars on their way to a drive-in on Alpha Centauri. Tron is proof positive that the computer programmer’s art is racing alongside the animator’s art at Warp Factor Five. It’s no accident that the movie was brought to the screen by Walt Disney Productions, because old Walt was a true visionary. If he were alive today, he’d probably proclaim Tron his most exciting project since the days of the Davy Crockett coonskin cap.

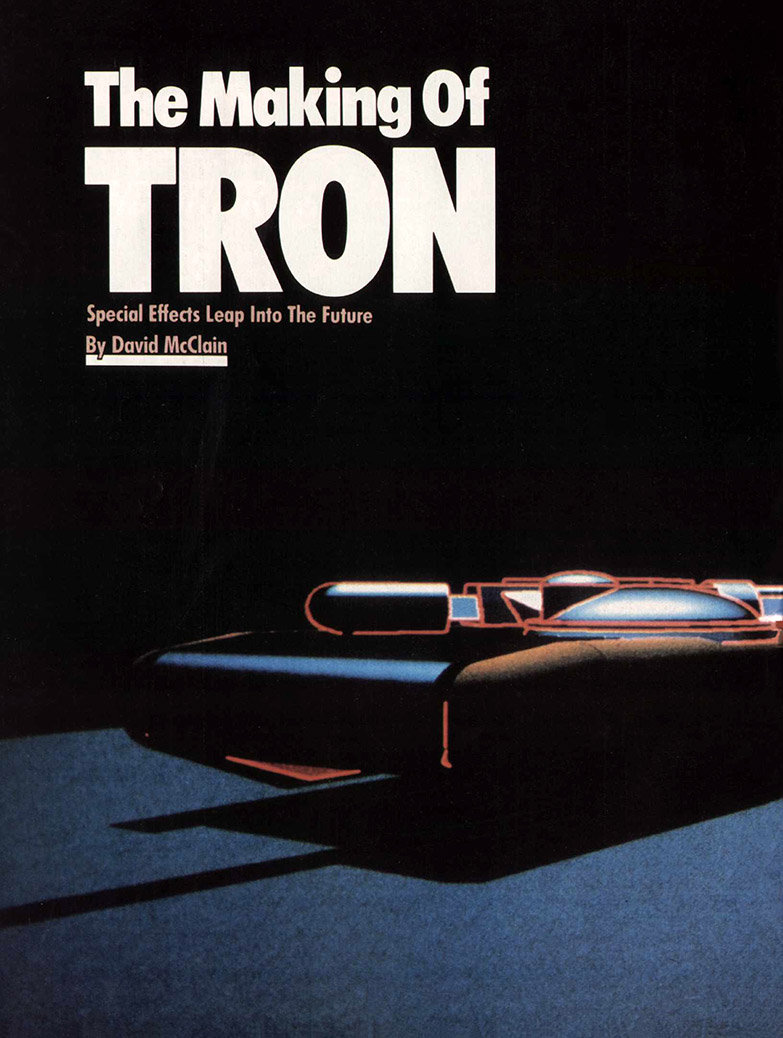

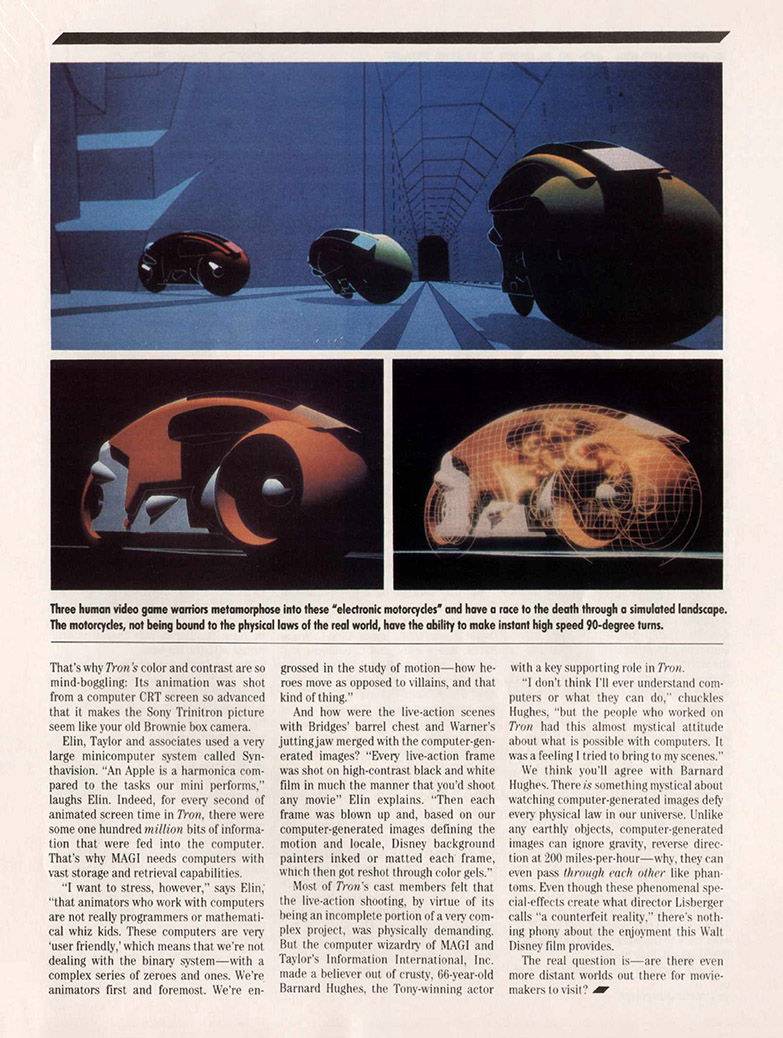

Without taking anything away from the cast, which include Jeff Bridges, Bruce Boxleitner and David Warner, the unique thing about Tron is that you’re looking at ideas, not models. In Star Wars, the warships piloted by Luke and Darth Vader were in fact tiny models photographed by a computer-controlled moving camera. But in Tron, there aren’t any models at all. The motion is conceived and captured by an imaginary “camera” defined by the computer. The real camera is only used to take a picture of the frame-by-frame action choreographed by the computer’s imaginary camera.

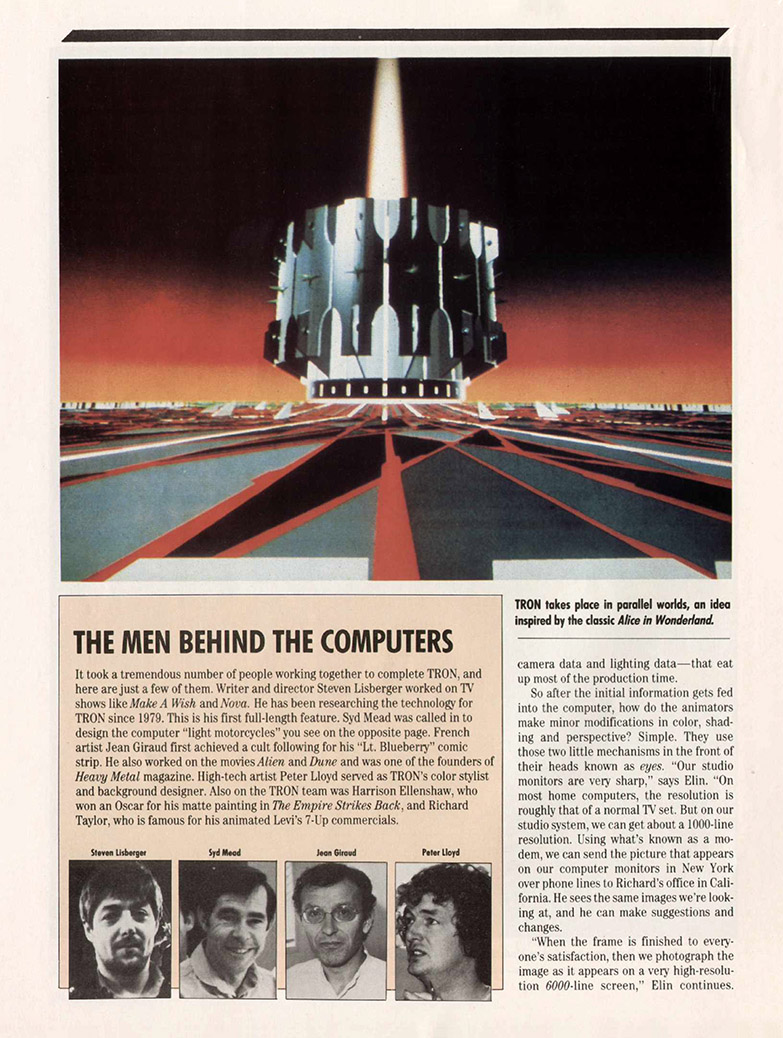

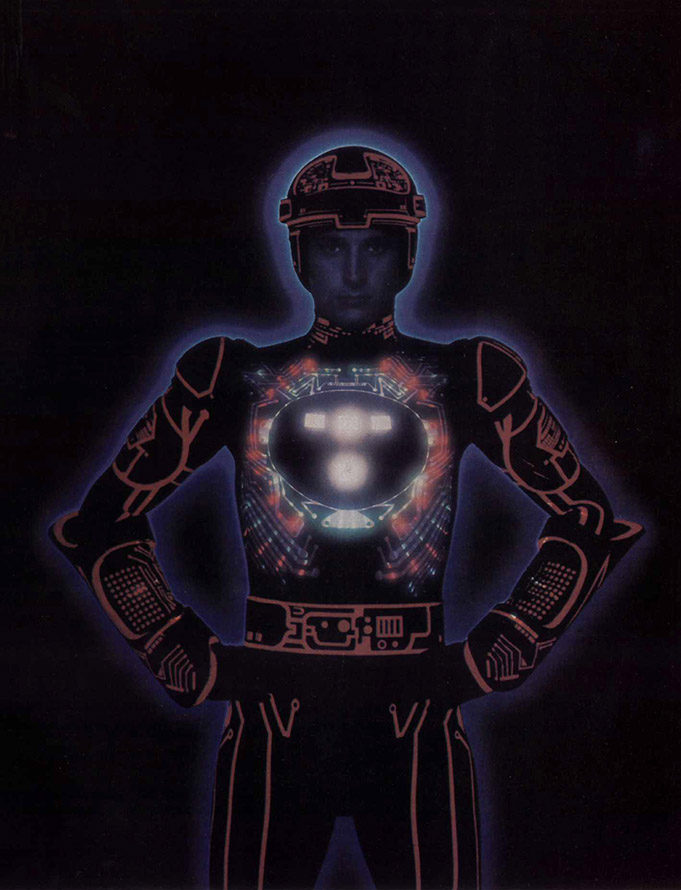

Tron is a futuristic adventure, naturally. which takes place in parallel worlds. It begins in the real world, which is rife with powerful computerized corporations such as ENCOM, an evil outfit that’s trying to patch into the Pentagon’s computers. This corporate mob is run by the aptly named villain, Dillinger (David Warner), who makes life miserable for a rebellious ENCOM employee (Bruce Boxleitner) and Flynn, a brilliant arcade owner (Jeff Bridges). Dillinger has perfected a laser which is capable of turning flesh-and-blood humans into electronic splat. Flynn gets “sucked into” this parallel world in which the computer user actually becomes his program. Bridges character awakens to discover that he’s been sentenced to death on a video game grid. His only ally is a warrior named Tron, who is actually the alter ego of the ENCOM programmer who’s fighting Dillinger in the “real” world.

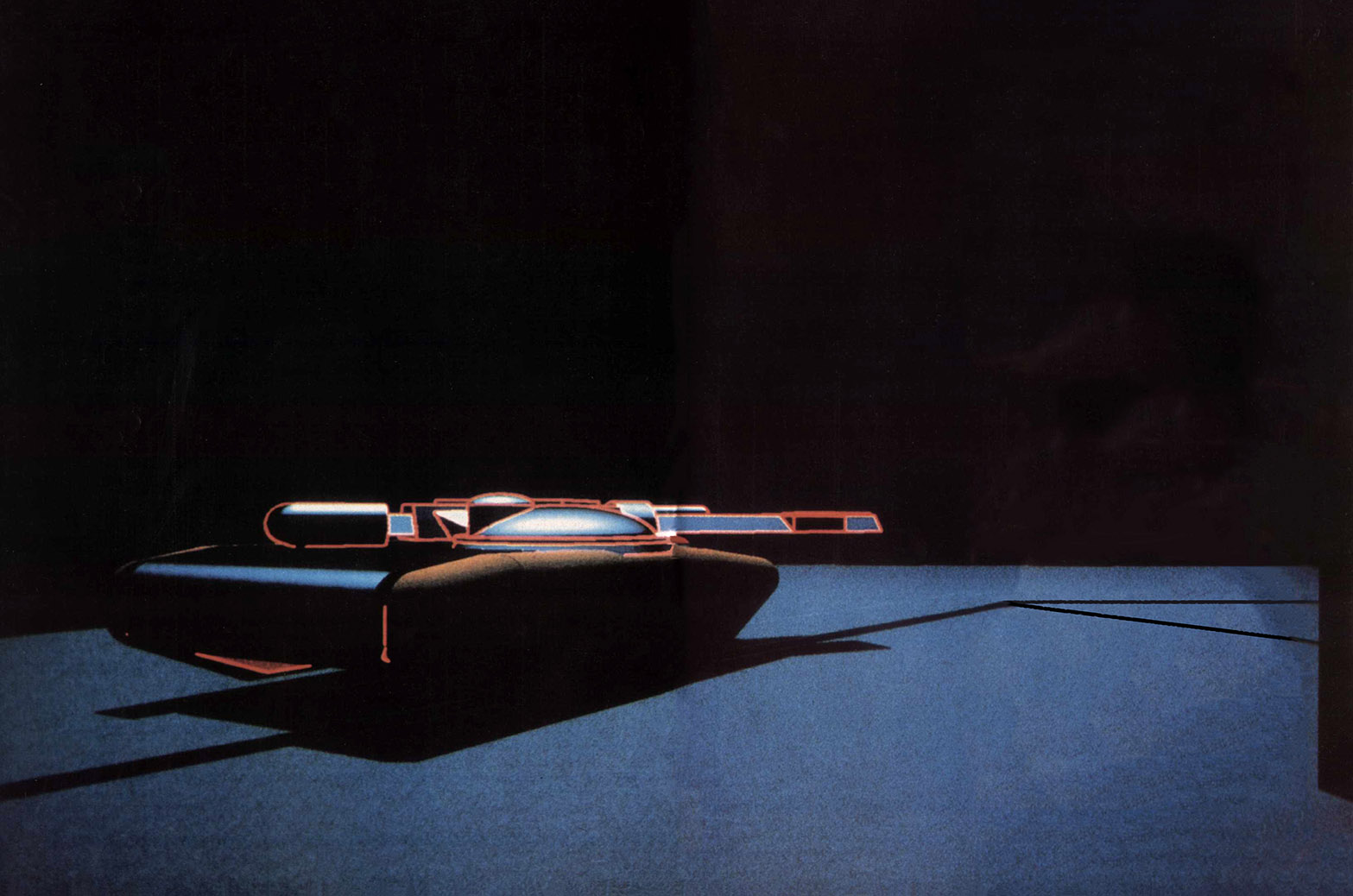

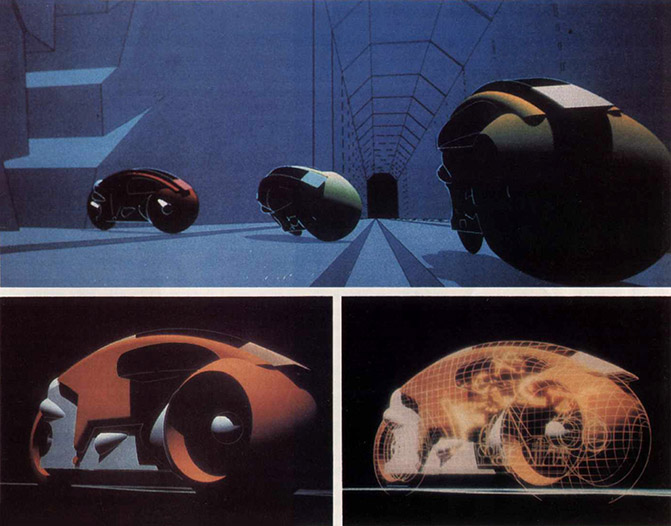

The laws of motion are completely different in this electronic world. When Tron and Flynn flee the villains on “electronic light cycles”, the getaway vehicles look a lot like plain old motorcycles. But they move with the freedom and fury of electrons, making incredible high-speed turns at 90 degree angles!

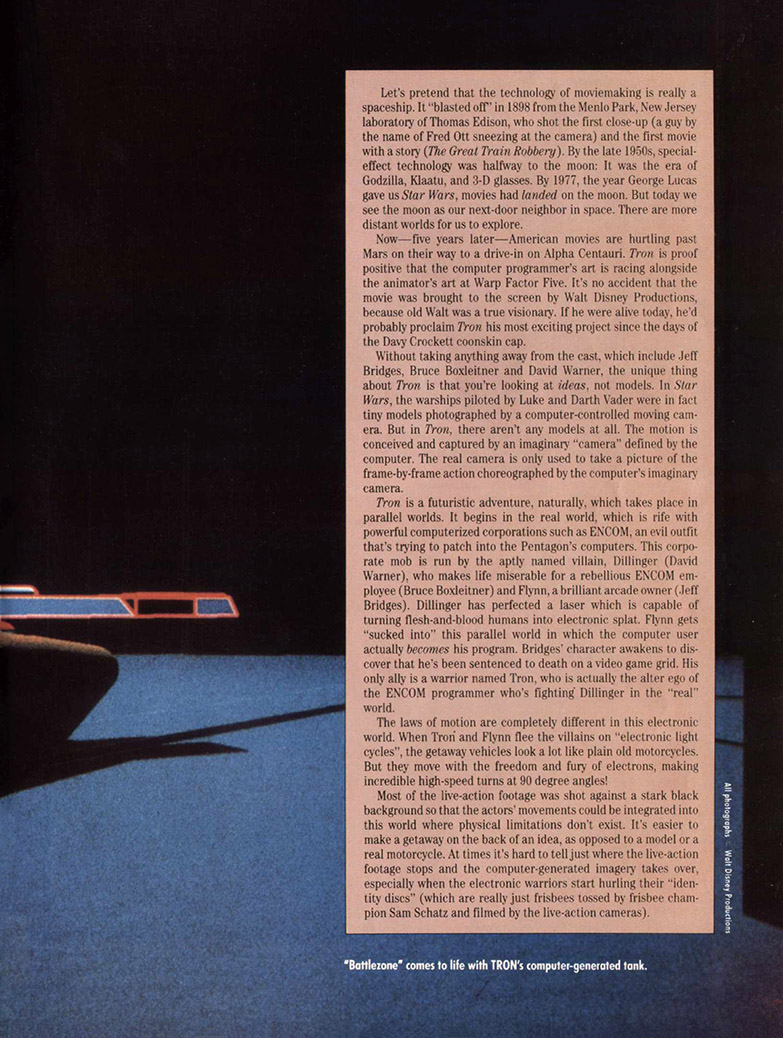

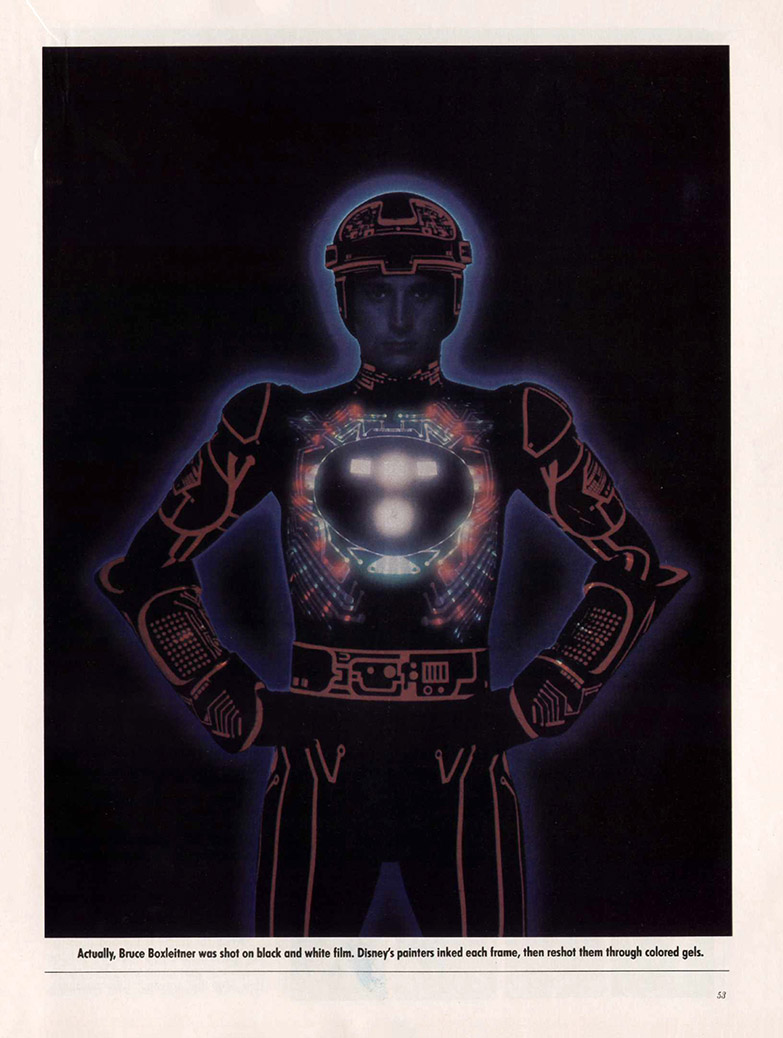

Most of the live-action footage was shot against a stark black background so that the actors’ movements could be integrated into this world where physical limitations don’t exist. It’s easier to make a getaway on the back of an idea, as opposed to a model or a real motorcycle. At times it’s hard to tell just where the live-action footage stops and the computer-generated imagery takes over, especially when the electronic warriors start hurling their “identity discs” (which are really just frisbees tossed by frisbee champion Sam Schatz and filmed by the live-action cameras).

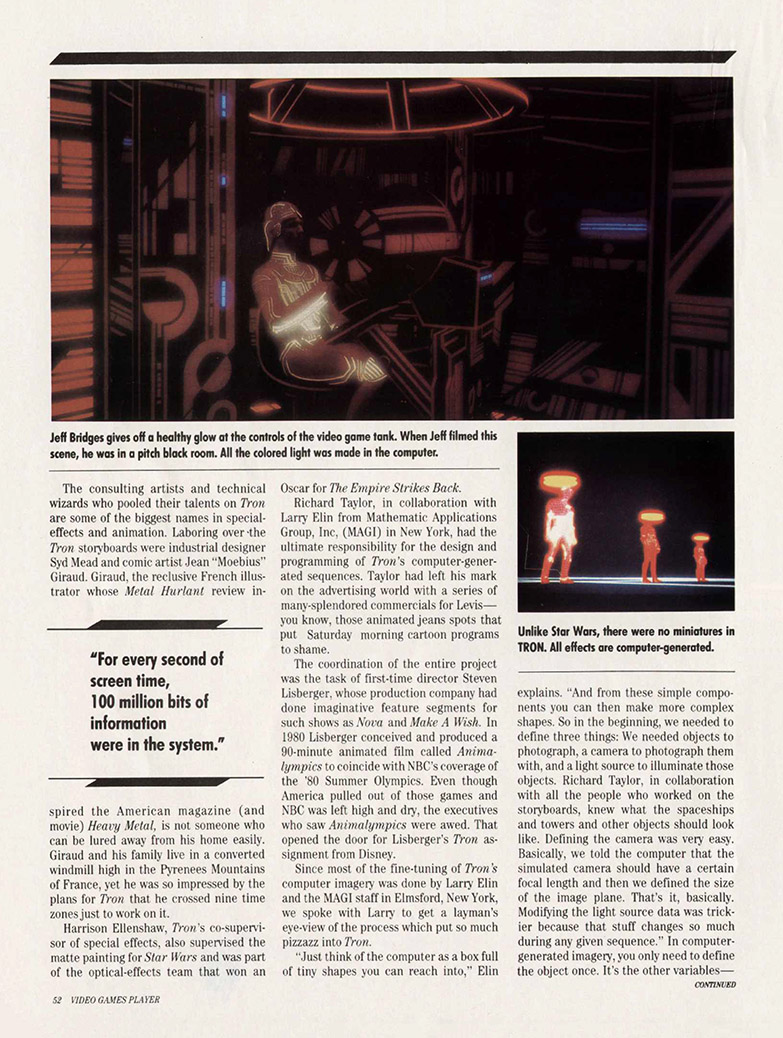

The consulting artists and technical wizards who pooled their talents on Tron are some of the biggest names in special-effects and animation. Laboring over the Tron storyboards were industrial designer Syd Mead and comic artist Jean “Moebius” Giraud. Giraud, the reclusive French illustrator whose Metal Hurlant review inspired the American magazine (and movie) Heavy Metal, is not someone who can be lured away from his home easily. Giraud and his family live in a converted windmill high in the Pyrenees Mountains of France, yet he was so impressed by the plans for Tron that he crossed nine time zones just to work on it.

Harrison Ellenshaw, Tron’s co-supervisor of special effects, also supervised the matte painting for Star Wars and was part of the optical-effects team that won an Oscar for The Empire Strikes Back.

Richard Taylor, in collaboration with Larry Elin from Mathematic Applications Group, Inc, (MAGI) in New York, had the ultimate responsibility for the design and programming of Tron’s computer-generated sequences. Taylor had left his mark on the advertising world with a series of many-splendored commercials for Levis—you know, those animated jeans spots that put Saturday morning cartoon programs to shame.

The coordination of the entire project was the task of first-time director Steven Lisberger, whose production company had done imaginative feature segments for such shows as Nova and Make A Wish. In 1980 Lisberger conceived and produced a 90-minute animated film called Animalympics to coincide with NBC’s coverage of the ‘80 Summer Olympics. Even though America pulled out of those games and NBC was left high and dry, the executives who saw Animalympics were awed. That opened the door for Lisberger’s Tron assignment from Disney.

Since most of the fine-tuning of Tron’s computer imagery was done by Larry Elin and the MAGI staff in Elmsford, New York, we spoke with Larry to get a layman’s eye-view of the process which put so much pizzazz into Tron.

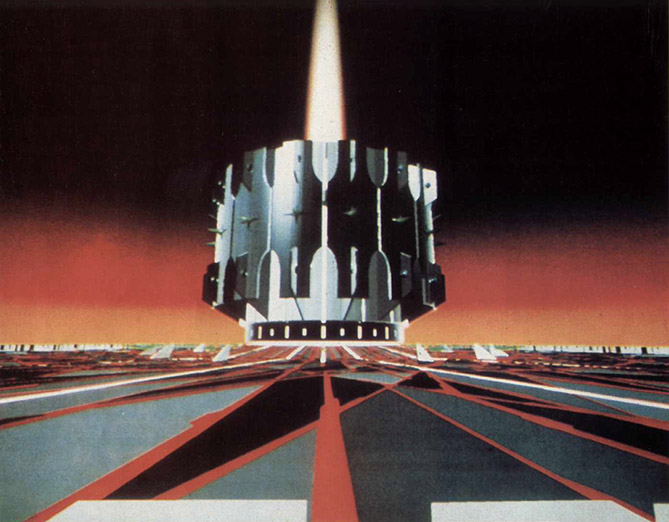

“Just think of the computer as a box full of tiny shapes you can reach into,” Elin explains. “And from these simple components you can then make more complex shapes. So in the beginning, we needed to define three things: We needed objects to photograph, a camera to photograph them with, and a light source to illuminate those objects. Richard Taylor, in collaboration with all the people who worked on the storyboards, knew what the spaceships and towers and other objects should look like. Defining the camera was very easy. Basically, we told the computer that the simulated camera should have a certain focal length and then we defined the size of the image plane. That’s it, basically. Modifying the light source data was trickier because that stuff changes so much during any given sequence.” In computer-generated imagery, you only need to define the object once. It’s the other variables—camera data and lighting data—that eat up most of the production time.

So after the initial information gets fed into the computer, how do the animators make minor modifications in color, shading and perspective? Simple. They use those two little mechanisms in the front of their heads known as eyes. “Our studio monitors are very sharp,” says Elin. “On most home computers, the resolution is roughly that of a normal TV set. But on our studio system, we can get about a 1000-line resolution. Using what’s known as a modem, we can send the picture that appears on our computer monitors in New York over phone lines to Richard’s office in California. He sees the same images we’re looking at, and he can make suggestions and changes.

“When the frame is finished to everyone’s satisfaction, then we photograph the image as it appears on a very high-resolution 6000-line screen,” Elin continues. That’s why Tron’s color and contrast are so mind-boggling: Its animation was shot from a computer CRT screen so advanced that it makes the Sony Trinitron picture seem like your old Brownie box camera.

Elin, Taylor and associates used a very large minicomputer system called Synthavision. “An Apple is a harmonica compared to the tasks our mini performs,” laughs Elin. Indeed, for every second of animated screen time in Tron, there were some one hundred million bits of information that were fed into the computer. That’s why MAGI needs computers with vast storage and retrieval capabilities.

“I want to stress, however,” says Elin, “that animators who work with computers are not really programmers or mathematical whiz kids. These computers are very ‘user friendly,’ which means that we’re not dealing with the binary system—with a complex series of zeroes and ones. We’re animators first and foremost. We’re engrossed in the study of motion—how heroes move as opposed to villains, and that kind of thing.”

And how were the live-action scenes with Bridges’ barrel chest and Warner’s jutting jaw merged with the computer-generated images? “Every live-action frame was shot on high-contrast black and white film in much the manner that you’d shoot any movie” Elin explains. “Then each frame was blown up and, based on our computer-generated images defining the motion and locale, Disney background painters inked or matted each frame, which then got reshot through color gels.”

Most of Tron’s cast members felt that the live-action shooting, by virtue of its being an incomplete portion of a very complex project, was physically demanding. But the computer wizardry of MAGI and Taylor’s Information International, Inc. made a believer out of crusty, 66-year-old Barnard Hughes, the Tony-winning actor with a key supporting role in Tron.

“I don’t think I’ll ever understand computers or what they can do,” chuckles Hughes, “but the people who worked on Tron had this almost mystical attitude about what is possible with computers. It was a feeling I tried to bring to my scenes.”

We think you’ll agree with Barnard Hughes. There is something mystical about watching computer-generated images defy every physical law in our universe. Unlike any earthly objects, computer-generated images can ignore gravity, reverse direction at 200 miles-per-hour—why, they can even pass through each other like phantoms. Even though these phenomenal special-effects create what director Lisberger calls “a counterfeit reality,” there’s nothing phony about the enjoyment this Walt Disney film provides.

The real question is—are there even more distant worlds out there for moviemakers to visit?

THE MEN BEHIND THE COMPUTERS

Lisberger

Mead

Giraud

Lloyd

It took a tremendous number of people working together to complete TRON, and here are just a few of them. Writer and director Steven Lisberger worked on TV shows like Make A Wish and Nova. He has been researching the technology for TRON since 1979. This is his first full-length feature. Syd Mead was called in to design the computer “light motorcycles” you see on the opposite page. French artist Jean Giraud first achieved a cult following for his “Lt. Blueberry” comic strip. He also worked on the movies Alien and Dune and was one of the founders of Heavy Metal magazine. High-tech artist Peter Lloyd served as TRON’s color stylist and background designer. Also on the TRON team was Harrison Ellenshaw, who won an Oscar for his matte painting in The Empire Strikes Back, and Richard Taylor, who is famous for his animated Levi’s 7-Up commercials.

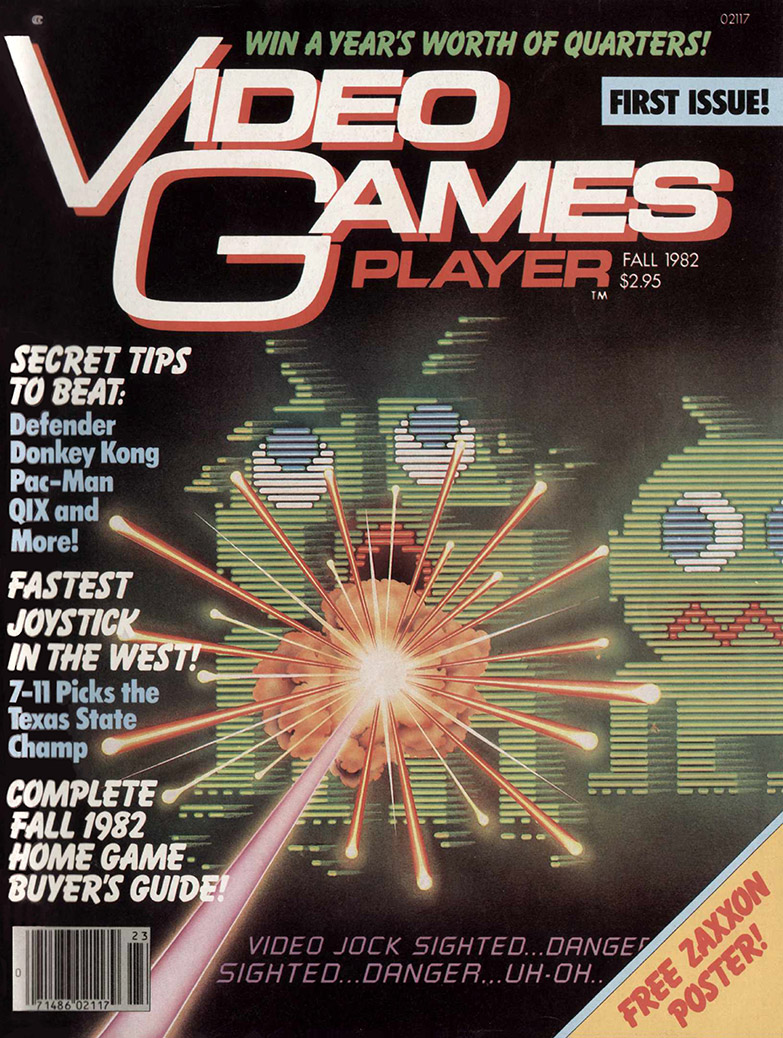

Source Pages