Programmable Parade

Go On Safari with the King of Swing!

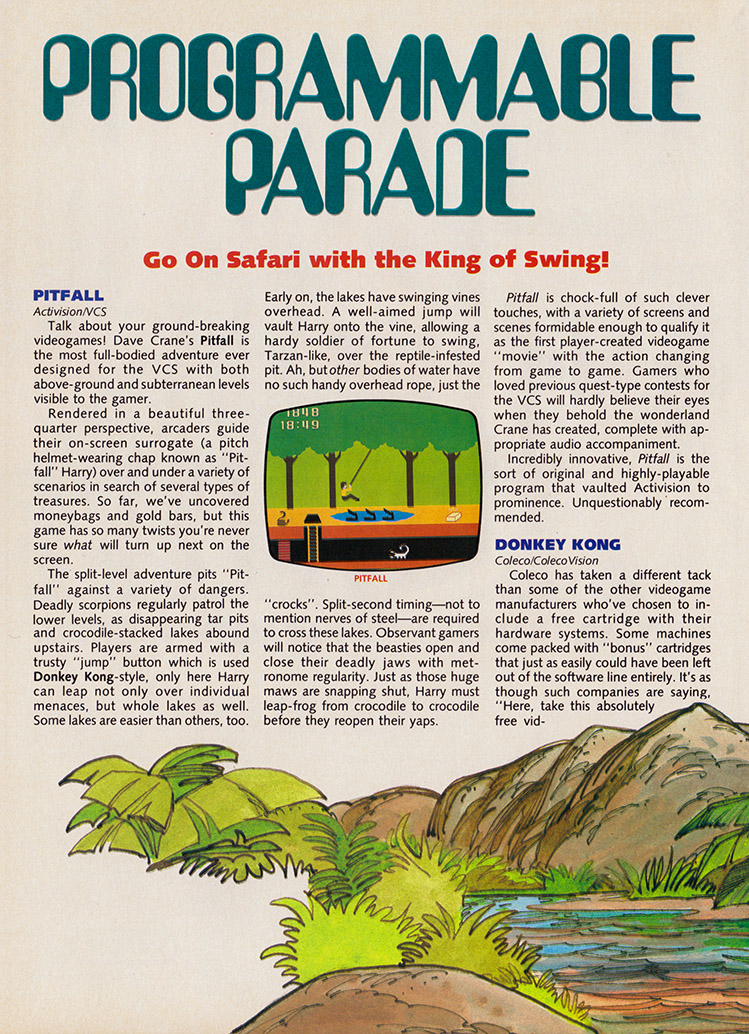

PITFALL

Activision/VCS

Talk about your ground-breaking videogames! Dave Crane’s Pitfall is the most full-bodied adventure ever designed for the VCS with both above-ground and subterranean levels visible to the gamer.

Rendered in a beautiful three quarter perspective, arcaders guide their on-screen surrogate (a pitch helmet-wearing chap known as “Pitfall” Harry) over and under a variety of scenarios in search of several types of treasures. So far, we’ve uncovered moneybags and gold bars, but this game has so many twists you’re never sure what will turn up next on the screen.

The split-level adventure pits “Pitfall” against a variety of dangers. Deadly scorpions regularly patrol the lower levels, as disappearing tar pits and crocodile-stacked lakes abound upstairs. Players are armed with a trusty “jump” button which is used Donkey Kong-style, only here Harry can leap not only over individual menaces, but whole lakes as well. Some lakes are easier than others, too. Early on, the lakes have swinging vines overhead. A well-aimed jump will vault Harry onto the vine, allowing a hardy soldier of fortune to swing, Tarzan-like, over the reptile-infested pit. Ah, but other bodies of water have no such handy overhead rope, just the “crocks”. Split-second timing—not to mention nerves of steel—are required to cross these lakes. Observant gamers will notice that the beasties open and close their deadly jaws with metronome regularity. Just as those huge maws are snapping shut, Harry must leap-frog from crocodile to crocodile before they reopen their yaps.

Pitfall is chock-full of such clever touches, with a variety of screens and scenes formidable enough to qualify it as the first player-created videogame “movie” with the action changing from game to game. Gamers who loved previous quest-type contests for the VCS will hardly believe their eyes when they behold the wonderland Crane has created, complete with appropriate audio accompaniment.

Incredibly innovative, Pitfall is the sort of original and highly-playable program that vaulted Activision to prominence. Unquestionably recommended.

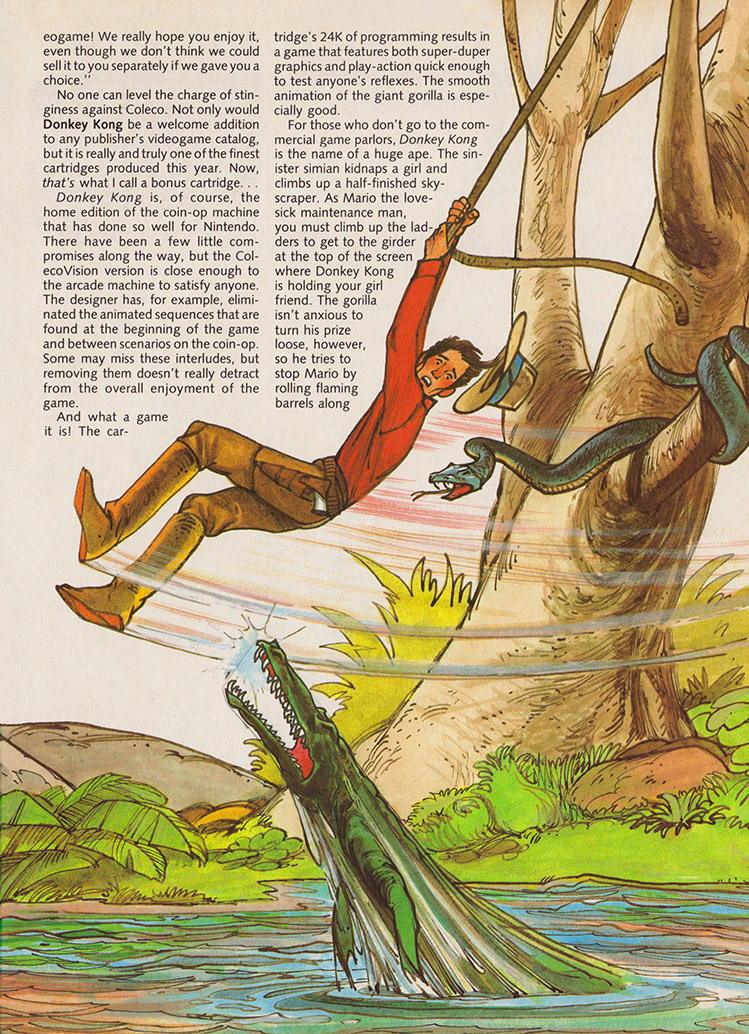

DONKEY KONG

Coleco/ColecoVision

Coleco has taken a different tack than some of the other videogame manufacturers who’ve chosen to include a free cartridge with their hardware systems. Some machines come packed with “bonus” cartridges that just as easily could have been left out of the software line entirely. It’s as though such companies are saying, “Here, take this absolutely free videogame! We really hope you enjoy it, even though we don’t think we could sell it to you separately if we gave you a choice.”

No one can level the charge of stinginess against Coleco. Not only would Donkey Kong be a welcome addition to any publisher’s videogame catalog, but it is really and truly one of the finest cartridges produced this year. Now, that’s what I call a bonus cartridge.

Donkey Kong is, of course, the home edition of the coin-op machine that has done so well for Nintendo. There have been a few little compromises along the way, but the ColecoVision version is close enough to the arcade machine to satisfy anyone. The designer has, for example, eliminated the animated sequences that are found at the beginning of the game and between scenarios on the coin-op. Some may miss these interludes, but removing them doesn’t really detract from the overall enjoyment of the game.

And what a game it is! The cartridge’s 24K of programming results in a game that features both super-duper graphics and play-action quick enough to test anyone’s reflexes. The smooth animation of the giant gorilla is especially good.

For those who don’t go to the commercial game parlors, Donkey Kong is the name of a huge ape. The sinister simian kidnaps a girl and climbs up a half-finished skyscraper. As Mario the lovesick maintenance man, you must climb up the ladders to get to the girder at the top of the screen where Donkey Kong is holding your girlfriend. The gorilla isn’t anxious to turn his prize loose, however, so he tries to stop Mario by rolling flaming barrels along the girders at the would-be savior.

Mario has two ways to stop this attack. He can either leap over the barrel—done by pushing the left-side action button—or smash it with one of the hammers which hang conveniently from the undersides of two girders. If Mario leaps up and snags the hammer, he has roughly 20 seconds in which he can break any casks that rumble his way. To keep the game from getting too unbalanced in Mario’s favor, the designer prevents him from being able to climb while the hammer’s active. Of course, you can position Mario right at the bottom of a ladder while the hammer flails away and then scoot to the next girder when it disappears, but such maneuvers still run some risk.

At the easiest skill level, you have five Mario’s to send scrambling up the ladders one at a time. If one is eliminated, the next one starts right at the beginning.

On the other hand, if Mario makes it to the top, Donkey Kong snatches up the girl and climbs to a higher perch on the building. In the second scenario, Mario must remove bolts which are holding Donkey Kong’s roost in position by leaping over them. This level also introduces bonus prizes in the form of several of the girlfriend’s possessions. They are scattered around the second and third screens, and Mario scores extra points any time he touches one.

Removing all the bolts dislodges the big ape, but even this setback won’t finish the monstrous monkey. He just picks up his victim and climbs still higher to the third—and final—screen. This time, there are elevators among the girders and Mario will have to hop from one to the next in order to get to the top of the playfield where he can, at long last, rescue the poor woman.

Once the easiest difficulty setting is mastered, this three-phase game can be played at three more progressively difficult levels. Each difficulty level is usable in both one- and two-player contests.

Donkey Kong, in short, is one “gift horse” you won’t mind looking right in the mouth. It makes a fine beginning for the ColecoVision system.

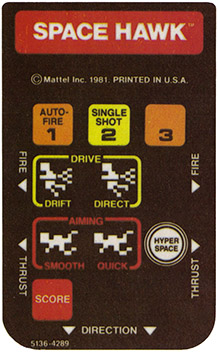

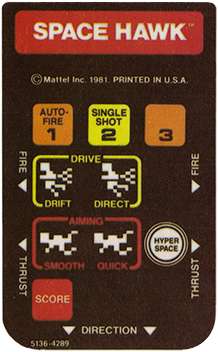

SPACE HAWK

Mattell/Intellivision

Since running out of topics for sports simulations—and discovering that, no matter how true-to-life they may be, sports-oriented videogames don’t have the mass appeal of SF and/or arcade titles—Mattel has started churning out a series of partially-successful but generally frustrating action con tests. Space Hawk, the latest in the series, offers an intriguing, and totally unique, play concept. Rather than manning a spaceship and then blowing away aliens, asteroids, et al, Space Hawk offers gamers the appealing proposition of manning a…well, a man.

Drifting through space, propelled by a thruster jet-pack and armed with a rifle-like weapon that shoots fireballs, gamers manipulate a stranded human space-soldier. The enemy consists of a flight of android space hawks and deadly, floating bubbles of poisonous gas.

Okay, now you’re all waiting to hear our usual song-and-dance regarding the inadequacy of the Intellivision controllers for action-style gaming, right? So it won’t be necessary for us to tell you that the disc will inevitably cause problems in controlling your star-spanning space avenger. What might surprise you, however, is our disappointment in the graphics themselves. The space soldier is so badly rendered that it becomes necessary to play the game in the Astrosmash-style “auto-fire” mode. Only by monitoring the source of the laser-balls being constantly fired, will average gamers be able to tell exactly in which direction the on-screen surrogate is facing!

Another problem is the inadequate sound effects. Despite evidence to the contrary—several new Intellivision-compatible Imagic videogames offer incredibly realistic audio—gamers might well think that the only explosive-like sound the system is capable of producing is the cap-pistol crack sound Intellivisionaries have been listening to since Space Battle. This anemic accompaniment doesn’t cut the cheese anymore. The audio for the soldier’s fireball weapon, on the other hand, is a wonderfully evocative whoosh that almost single-handedly carries this cartridge-along with the excellent fireballs themselves, and the fine, robotic animation of the space hawks.

Since this is, essentially, a prettied-up version of Asteroids, it should have been a lot prettier. Instead, weak graphics and mediocre control turn take yet another potential smash into a flawed but interesting contest. The concept of controlling a jet-pack space grunt is, of itself, fascinating enough to keep Intellivision fans satisfied. Nonetheless, it is undeniably sad to see no sign of improvement in the Intellivision line. The first cartridges remain the finest, while the same outfits’ programs for the much-criticized VCS show astonishing technical advances. The question still remains: Why haven’t the Mattel programmers/designers overcome problems that have plagued their software since they began producing action contests? Why is the first Intellivision science fiction game, Space Battle, still the best arcade-style title in the entire line? With the ever-increasing sophistication of both videogames and videogamers, standing still begins to look like going backwards—and that’s something no system can handle.

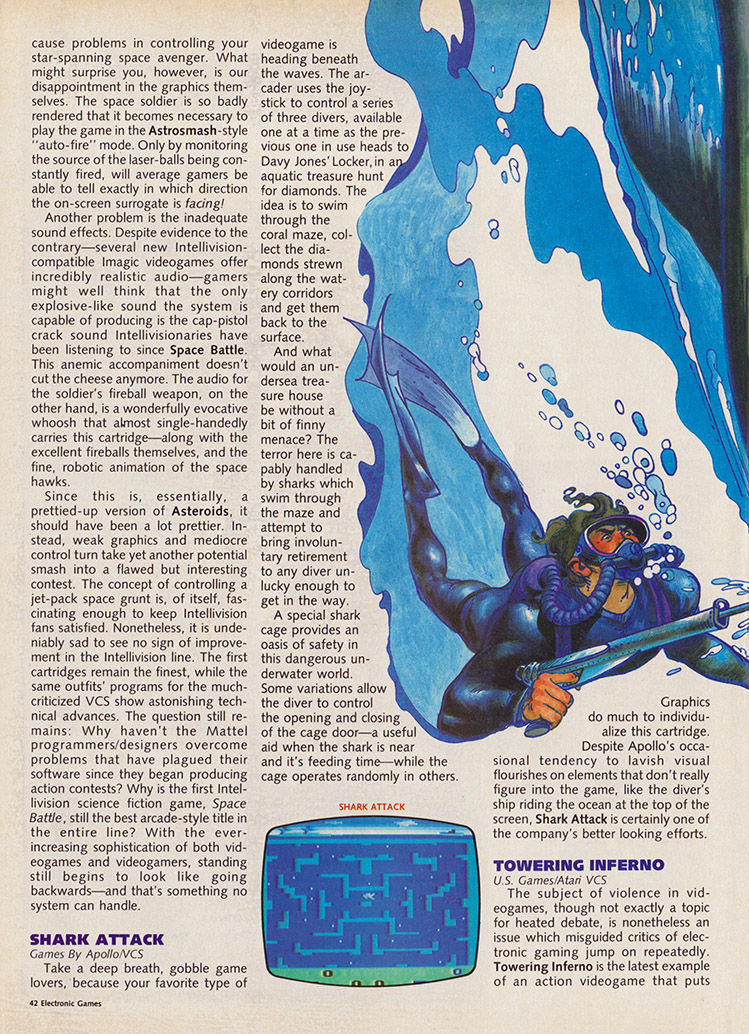

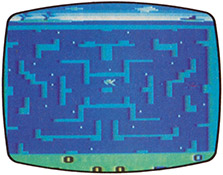

SHARK ATTACK

Games By Apollo/VCS

Take a deep breath, gobble game lovers, because your favorite type of videogame is heading beneath the waves. The arcader uses the joystick to control a series of three divers, available one at a time as the previous one in use heads to Davy Jones’ Locker, in a aquatic treasure hunt for diamonds. The idea is to swim through the coral maze, collect the diamonds strewn along the watery corridors and get them back to the surface.

And what would an undersea treasure house be without a bit of finny menace? The terror here is capably handled by sharks which swim through the maze and attempt to bring involuntary retirement to any diver unlucky enough to get in the way.

A special shark cage provides an oasis of safety in this dangerous underwater world. Some variations allow the diver to control the opening and closing of the cage door—a useful aid when the shark is near and it’s feeding time—while the cage operates randomly in others.

Graphics do much to individualize this cartridge. Despite Apollo’s occasional tendency to lavish visual flourishes on elements that don’t really figure into the game, like the diver’s ship riding the ocean at the top of the screen, Shark Attack is certainly one of the company’s better looking efforts.

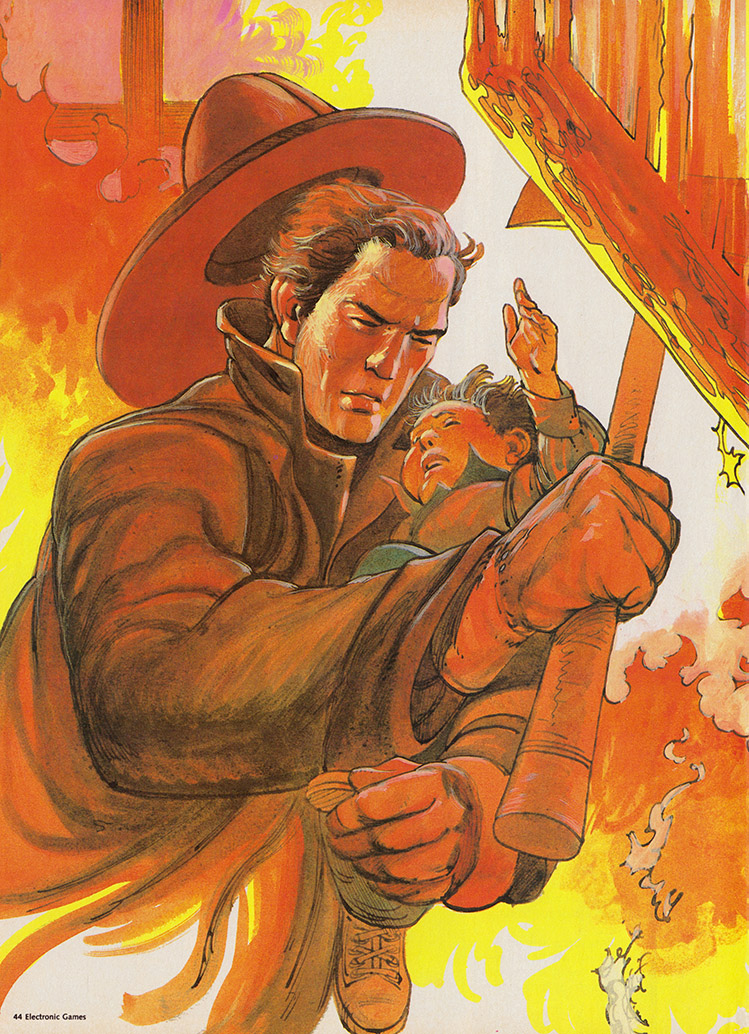

TOWERING INFERNO

U.S. Games/Atari VCS

The subject of violence in videogames, though not exactly a topic for heated debate, is nonetheless an issue which misguided critics of electronic gaming jump on repeatedly. Towering Inferno is the latest example of an action videogame that puts players in a thrilling situation without even the most abstract suggestion of mayhem. In Towering Inferno, the arcader is a fire fighter helicoptered to the roof of a burning building. Hose in hand, the fire fighter must work top floor, fighting and dodging the flames, to rescue the survivors. There are four people trapped at the top of the screen in each round, but they are overcome by the smoke one by one as the game’s clock ticks off precious seconds. The faster the gamer moves the on-screen character, the more people can be saved from a hideous flaming death.

The hose can spray a stream of water in the direction in which the nozzle is facing—either toward the top or bottom of the screen—by hitting the action button. Flames move back and forth from left to right. No amount of water can put out a flame that’s burning inside a wall, but the fire fighter can score one point for dousing a flame in a room or hallway. (Note: Playing with the difficulty switches in the “A” position turns the flames invisible when they’re in one of the walls. This makes it much harder to plan hose strategy, since there’s much less warning when the line of fire approaches your character.) The heavy point values, though, come from saving victims of the fire, so this must be the goal of anyone hoping to do really well at this cartridge.

Once the fire fighter threads a path up the playfield to where the survivors are waiting for help, he must turn around and lead them back down the screen toward the safety of the waiting helicopter. The whirlybird carries them off, and the fire fighter begins again on another floor. Play continues until either the whole building is under control or the player loses all three of his men. Of course, if you take too long, some floors already visited may burst into flames again, but that’s the breaks in the heroic game of fire fighting.

Like most cartridges for the VCS, Towering Inferno is stronger in action than its visual effects. The display is all right, though the images are certainly more symbolic than realistic. The water looks like its streaming from the hose, though more than one player will wish there was a way to exert finer control over the water.

In one sense, Towering Inferno is a victory for those who believe that manufacturers should, indeed, not rely so much on whizzing bullets to produce on-screen excitement. Towering Inferno plays something like a maze-shoot, even though there’s not so much as a single bullet fired in anger—even at totally evil alien monsters. Yet this cartridge is about as exciting as any videogame done along more traditional lines.

But let’s put all the philosophizing where it belongs—back into the storage cabinet with the unused cartridges. Towering Inferno, even apart from its low violence quotient, offers plenty of solid arcading. It’s fast, exciting and different enough from the typical cartridge to be of interest to VCS owners. It’s a well-done, enjoyable contest.

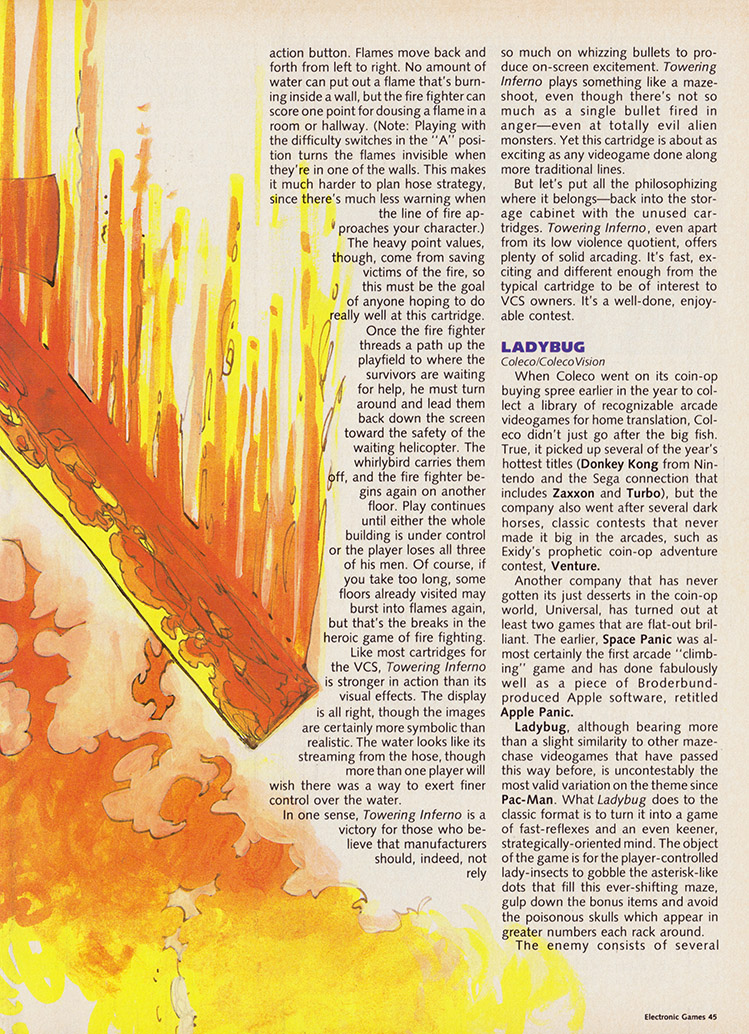

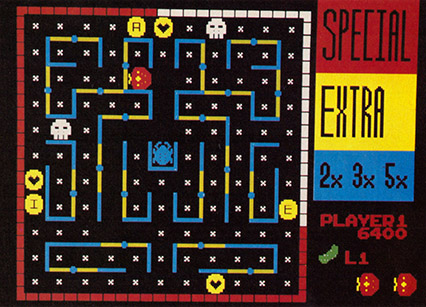

LADYBUG

Coleco/ColecoVision

When Coleco went on its coin-op buying spree earlier in the year to collect a library of recognizable arcade videogames for home translation, Coleco didn’t just go after the big fish. True, it picked up several of the year’s hottest titles (Donkey Kong from Nintendo and the Sega connection that includes Zaxxon and Turbo), but the company also went after several dark horses, classic contests that never made it big in the arcades, such as Exidy’s prophetic coin-op adventure contest, Venture.

Another company that has never gotten its just desserts in the coin-op world, Universal, has turned out at least two games that are flat-out brilliant. The earlier, Space Panic was almost certainly the first arcade “climbing” game and has done fabulously well as a piece of Broderbund produced Apple software, retitled Apple Panic.

Ladybug, although bearing more than a slight similarity to other maze-chase videogames that have passed this way before, is uncontestably the most valid variation on the theme since Pac-Man. What Ladybug does to the classic format is to turn it into a game of fast-reflexes and an even keener, strategically-oriented mind. The object of the game is for the player-controlled lady-insects to gobble the asterisk-like dots that fill this ever-shifting maze, gulp down the bonus items and avoid the poisonous skulls which appear in greater numbers each rack around.

The enemy consists of several species of nasty insect-life, from wasps to hungry beetles, all guarding—and emerging from—a tiny vegetable garden at the center of the screen, where each round presents a new, leafy bonus treat for your ravenous ladybugs. Four enemy bugs emerge from the garden each time a flashing light makes a complete revolution around the playfield. The poisonous skulls can also kill the hunter-insects, and there is no “energy dot”, a long-overused maze-chase convention. The Ladybug is strictly on her own, with only your quick wits to save the day.

Here’s the rub: the playfield includes not only maze corridors but also revolving, turnstile-like doorways, which only the ladybug can move. Skillful use of these turnstiles can trap the hunters, keep them at bay or backfire on the she-bug—even the best laid plans of arcaders and insects occasionally go astray, after all.

It’s the turnstiles, and the bonus-veggie that make Ladybug so addictive. Snatching up that green goodie even freezes the hunter insects in their tracks momentarily, giving your ladybug a chance for a strategic retreat to safer quarters.

How does the ColecoVision version stack up against the original? Hey, boys and girls, this is no shabby home-clone but a virtually perfect recreation of the Universal coin-op. The graphics are superb—as good as anything in the ColecoVision line so far with the exception of the unbelievable Smurf title, Escape from Gargamel’s Castle (which is only the most incredible bit of computer animation you’ve ever seen on a home TV). The sound effects are picture-perfect coin-op match-ups.

How does ColecoVision do it? Who cares—as long as they continue to produce rave-ups like this, rescuing abandoned classics from the arcade dust bin. An unqualified, glassy-eyed recommendation.

Take a bow, folks.

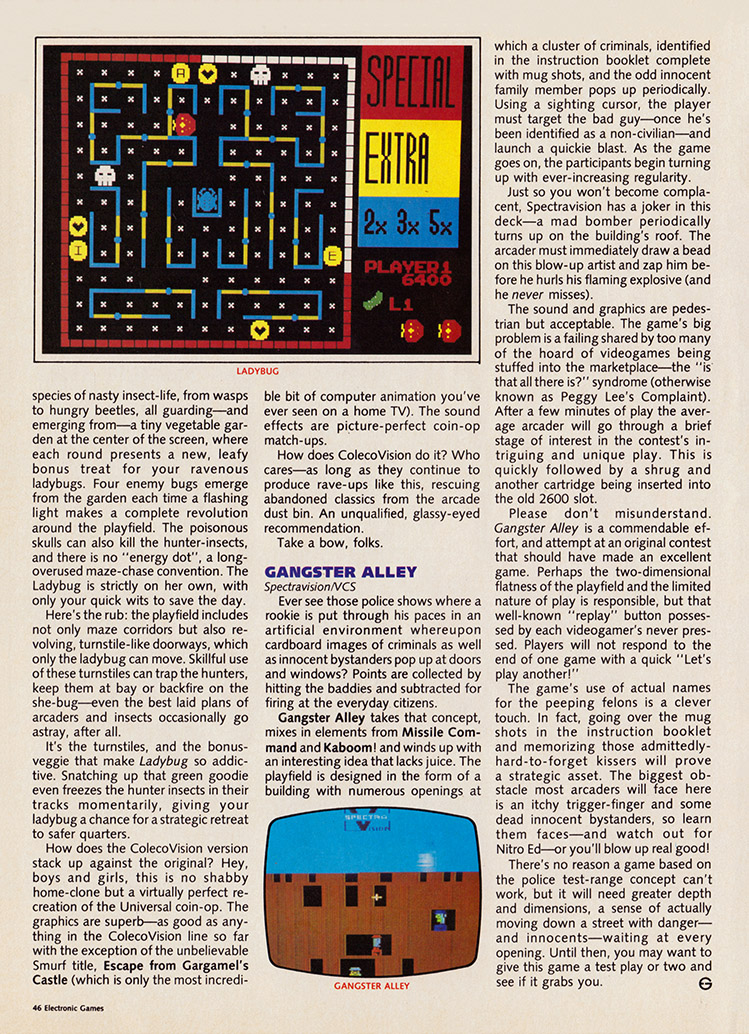

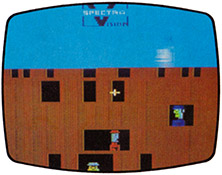

GANGSTER ALLEY

Spectravision/VCS

Ever see those police shows where a rookie is put through his paces in an artificial environment whereupon cardboard images of criminals as well as innocent bystanders pop up at doors and windows? Points are collected by hitting the baddies and subtracted for firing at the everyday citizens.

Gangster Alley takes that concept, mixes in elements from Missile Command and Kaboom! and winds up with an interesting idea that lacks juice. The playfield is designed in the form of a building with numerous openings at which a cluster of criminals, identified in the instruction booklet complete with mug shots, and the odd innocent family member pops up periodically. Using a sighting cursor, the player must target the bad guy—once he’s been identified as a non-civilian—and launch a quickie blast. As the game goes on, the participants begin turning up with ever-increasing regularity.

Just so you won’t become complacent, Spectravision has a joker in this deck—a mad bomber periodically turns up on the building’s roof. The arcader must immediately draw a bead on this blow-up artist and zap him before he hurls his flaming explosive (and he never misses).

The sound and graphics are pedestrian but acceptable. The game’s big problem is a failing shared by too many of the hoard of videogames being stuffed into the marketplace—the “is that all there is?” syndrome (otherwise known as Peggy Lee’s Complaint). After a few minutes of play the average arcader will go through a brief stage of interest in the contest’s intriguing and unique play. This is quickly followed by a shrug and another cartridge being inserted into the old 2600 slot.

Please don’t misunderstand. Gangster Alley is a commendable effort, and attempt at an original contest that should have made an excellent game. Perhaps the two-dimensional flatness of the playfield and the limited nature of play is responsible, but that well-known “replay” button possessed by each videogamer’s never pressed. Players will not respond to the end of one game with a quick “Let’s play another!”

The game’s use of actual names for the peeping felons is a clever touch. In fact, going over the mug shots in the instruction booklet and memorizing those admittedly-hard-to-forget kissers will prove a strategic asset. The biggest obstacle most arcaders will face here is an itchy trigger-finger and some dead innocent bystanders, so learn them faces—and watch out for Nitro Ed—or you’ll blow up real good!

There’s no reason a game based on the police test-range concept can’t work, but it will need greater depth and dimensions, a sense of actually moving down a street with danger—and innocents—waiting at every opening. Until then, you may want to give this game a test play or two and see if it grabs you.

Source Pages