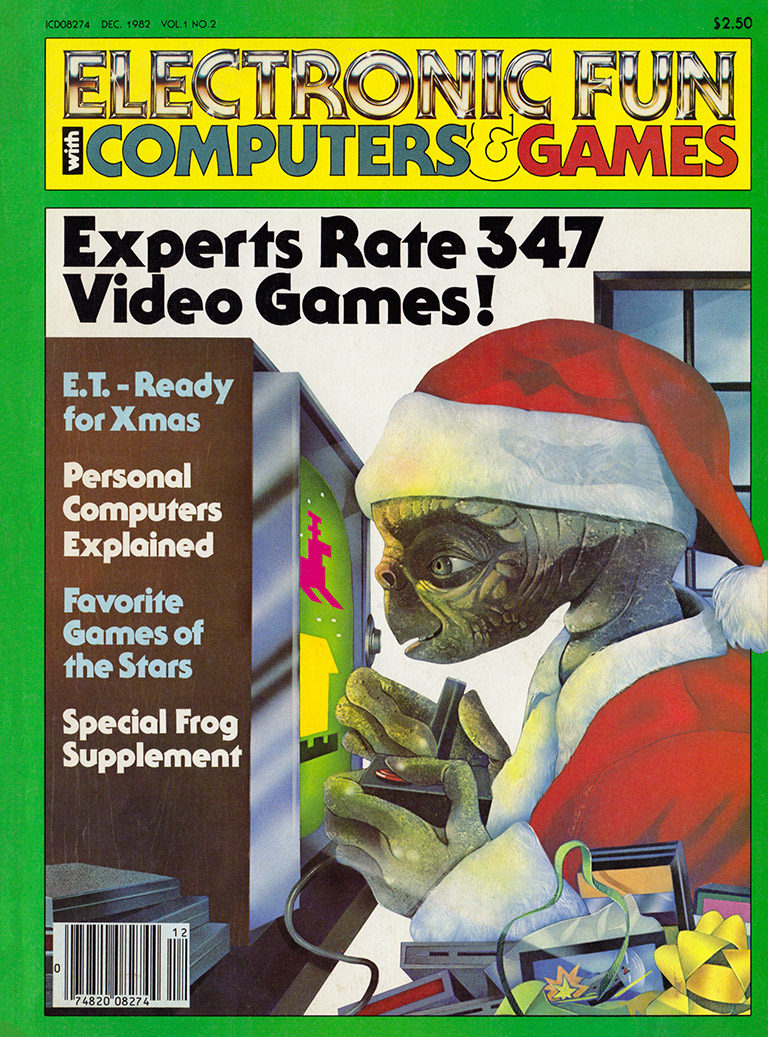

Gamemakers

The Good Doctor

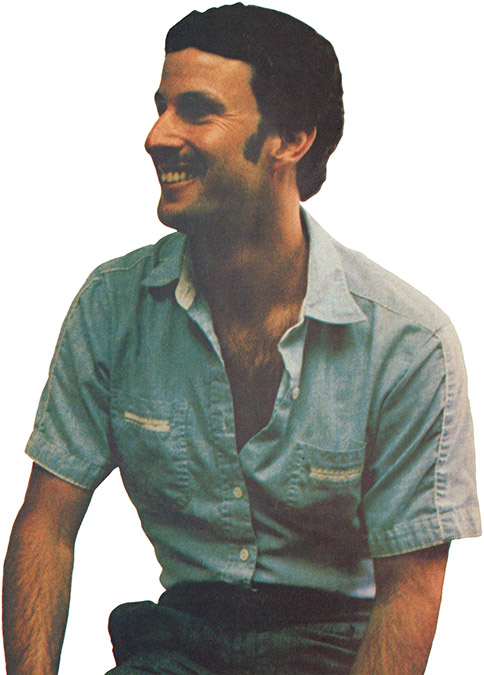

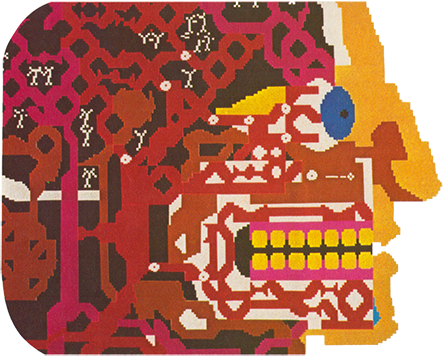

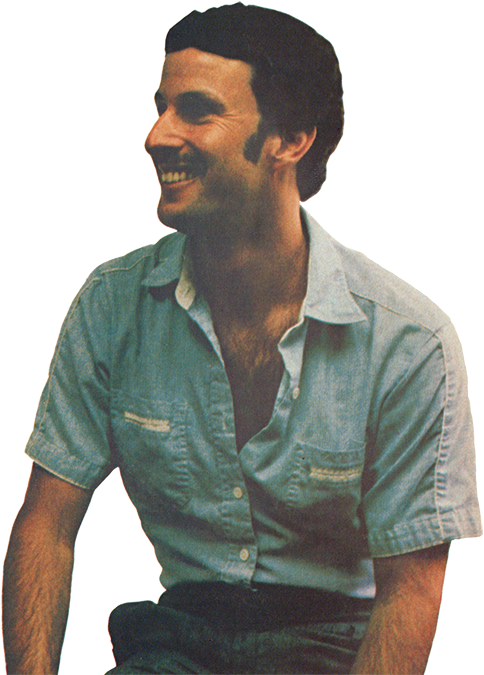

Imagic’s Rick Levine went from medicine to Micro Surgeon

Every so often a game comes along that is different than the average “run and gun, search for secret treasure” fare. Micro Surgeon is such a game. In this new Imagic game for Intellivision, you become a doctor without having to take the Hippocratic Oath or spend all those years (to say nothing of dollars) in medical school. In Micro Surgeon, you are transported, Fantastic Voyage-style, into the human body where you must cure one of over 200 patients of medical problems that range from kidney stones to brain tumors. Rick Levine conceived this offbeat game and we sat down with him and talked about video games, medicine and Micro Surgeon.

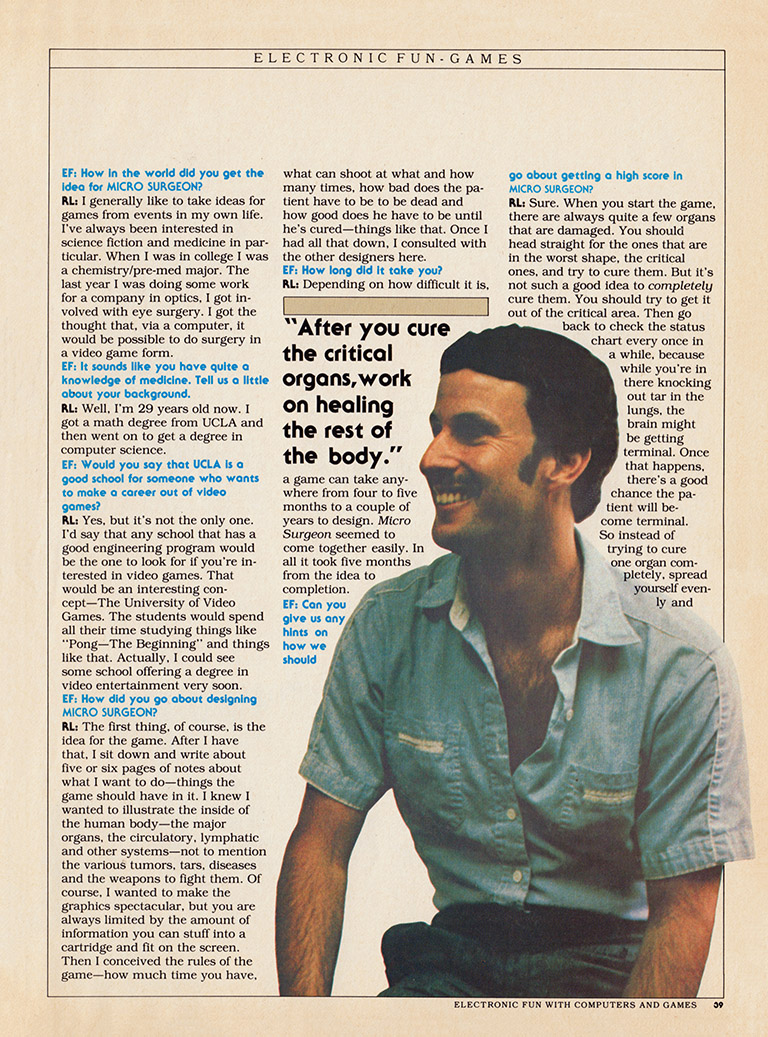

EF: How in the world did you get the idea for MICRO SURGEON?

RL: I generally like to take ideas for games from events in my own life. I’ve always been interested in science fiction and medicine in particular. When I was in college I was a chemistry/pre-med major. The last year I was doing some work for a company in optics, I got involved with eye surgery. I got the thought that, via a computer, it would be possible to do surgery in a video game form.

EF: It sounds like you have quite a knowledge of medicine. Tell us a little about your background.

RL: Well, I’m 29 years old now. I got a math degree from UCLA and then went on to get a degree in computer science.

EF: Would you say that UCLA is a good school for someone who wants to make a career out of video games?

RL: Yes, but it’s not the only one. I’d say that any school that has a good engineering program would be the one to look for if you’re interested in video games. That would be an interesting concept—The University of Video Games. The students would spend all their time studying things like “Pong—The Beginning” and things like that. Actually, I could see some school offering a degree in video entertainment very soon.

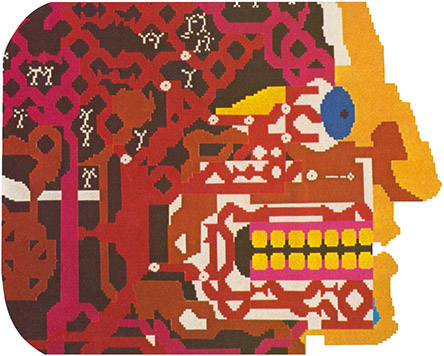

EF: How did you go about designing MICRO SURGEON?

RL: The first thing, of course, is the idea for the game. After I have that, I sit down and write about five or six pages of notes about what I want to do—things the game should have in it. I knew I wanted to illustrate the inside of the human body—the major organs, the circulatory, lymphatic and other systems—not to mention the various tumors, tars, diseases and the weapons to fight them. Of course, I wanted to make the graphics spectacular, but you are always limited by the amount of information you can stuff into a cartridge and fit on the screen. Then I conceived the rules of the game—how much time you have, what can shoot at what and how many times, how bad does the patient have to be to be dead and how good does he have to be until he’s cured—things like that. Once I had all that down, I consulted with the other designers here.

EF: How long did It take you?

RL: Depending on how difficult it is, a game can take anywhere from four to five months to a couple of years to design. Micro Surgeon seemed to come together easily. In all it took five months from the idea to completion.

EF: Can you give us any hints on how we should go about getting a high score in MICRO SURGEON?

RL: Sure. When you start the game, there are always quite a few organs that are damaged. You should head straight for the ones that are in the worst shape, the critical ones, and try to cure them. But it’s not such a good idea to completely cure them. You should try to get it out of the critical area. Then go back to check the status chart every once in a while, because while you’re in there knocking out tar in the lungs, the brain might be getting terminal. Once that happens, there’s a good chance the patient will become terminal.

So instead of trying to cure one organ completely, spread yourself evenly and conserve your shots because they use a lot of power.

Another good strategy tactic is that once something has gone terminal, the brain for instance, if you’re lucky enough not to have died yet, spend your time and effort on the other parts of the body. Once something has gone terminal, you can’t cure it anyway.

EF: What do you think are the elements of a good game?

RL: Number one, it has to be fun. Nobody’s going to play the game if it isn’t fun, and if nobody plays the game, it’s all over. But also, I think there should be some inherent value in a game. You should be able to get something out of it. It should teach you something, even if it’s only eye-hand coordination. You shouldn’t be able to play a game for a weekend and get tired of it.

EF: With that in mind, what do you consider your favorite game?

RL: Tough question. I can’t say I have one favorite game. Right now I’m playing Zaxxon a lot in arcades. In home games, it’s tough to top our own Demon Attack, designed by Rob Fulop for Atari and Gary Kape for Intellivision.

EF: Two separate designers worked out DEMON ATTACK?

RL: Sure. You can’t just take an Atari-compatible game and plug it into an Intellivision. The systems have very different graphics capabilities. A game has to be almost completely redesigned in order to put it out in the opposite format. Most designers are more familiar with one system over the other, so that’s why two designers work on separate formats of same game.

EF: Many of our readers probably would be Interested in doing what you do for a living—designing video games. What advice can you give them?

RL: The most important thing is that you know games, not just computers. You should really play every new game that comes out, home and arcade, to discover the idiosyncrasies of each. The more expanded your horizons are, the better. Of course, a computer science background is helpful, but there are a lot of designers with other backgrounds. It’s not how much you know about computers—it’s how good your game ideas are.

EF: What do you do when you’re not designing video games?

RL: I’m a sports enthusiast. I spend a lot of time playing tennis, golf and bowling.

EF: Are you married?

RL: Engaged.

EF: How does she feel, marrying a guy that makes games for kids as a living?

RL: She enjoys it. She herself doesn’t play video games much, but she likes the fact that I’m doing what I enjoy. Sometimes it’s better like that. After working all day with video games and other programmers, it’s nice to go out and talk about something else.

EF: Can you give us an idea of what your next game will be like?

RL: Naturally, I can’t tell you exactly about my next game because someone might be able to make a cheap copy and rush it out. One thing I can say about most games I might design is that there will be a definite uniqueness about them. I think Micro Surgeon’s biggest asset is that it’s different than any other game in the world. It’s not a space game, a maze game or an adventure game. Rather than taking a familiar game and trying to improve upon it, I like to think of new ideas and make the best games possible out of them. It’s much more difficult to design a game this way because you are breaking new ground—there is no precedent to base your judgment on. My next game will be very different than anything you’ve seen.

Source Pages