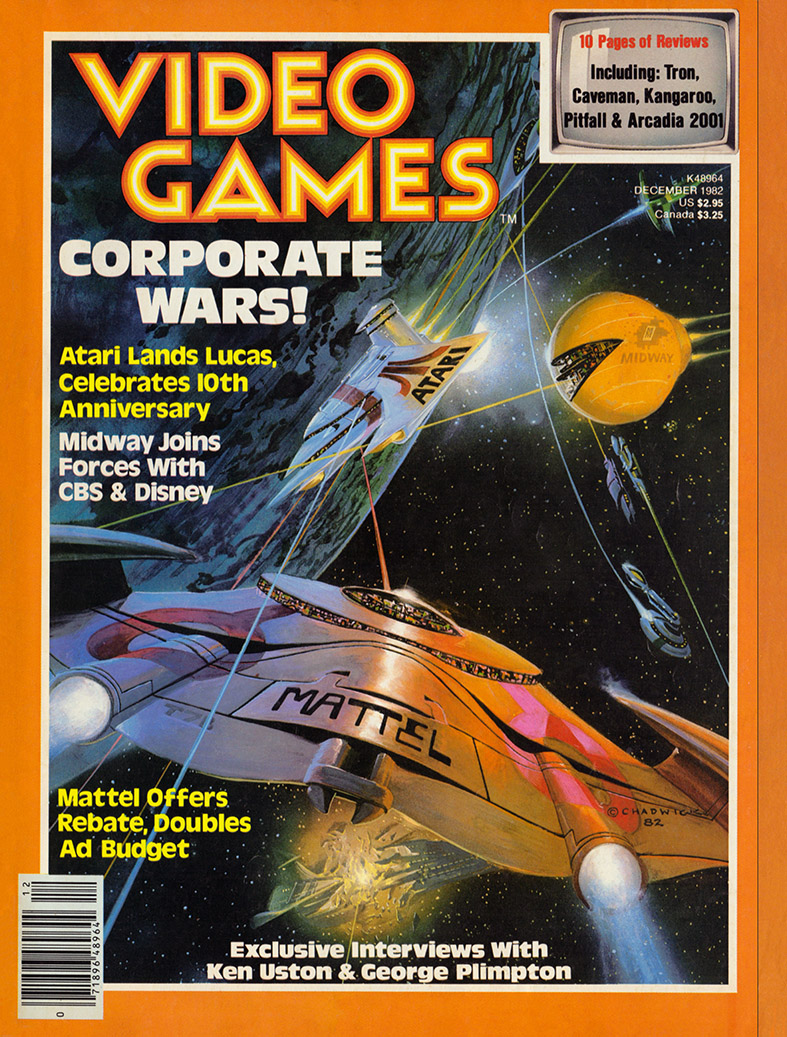

The Selling of Intellivision

Avis, Pepsi and Mattel have one thing in common: They all try harder. But trying harder gets to be trying after awhile. Pete Pirner, senior vice president of marketing at Mattel Electronics, knows the feeling.

“We make a better game than Atari—pure and simple,” he says boldly, referring to his company’s Intellivision and the competition’s Video Computer System (VCS). “Atari just happened to have gotten a three-year head start in the marketplace and was able to build up a larger installed base faster. That doesn’t necessarily make them a better game company.”

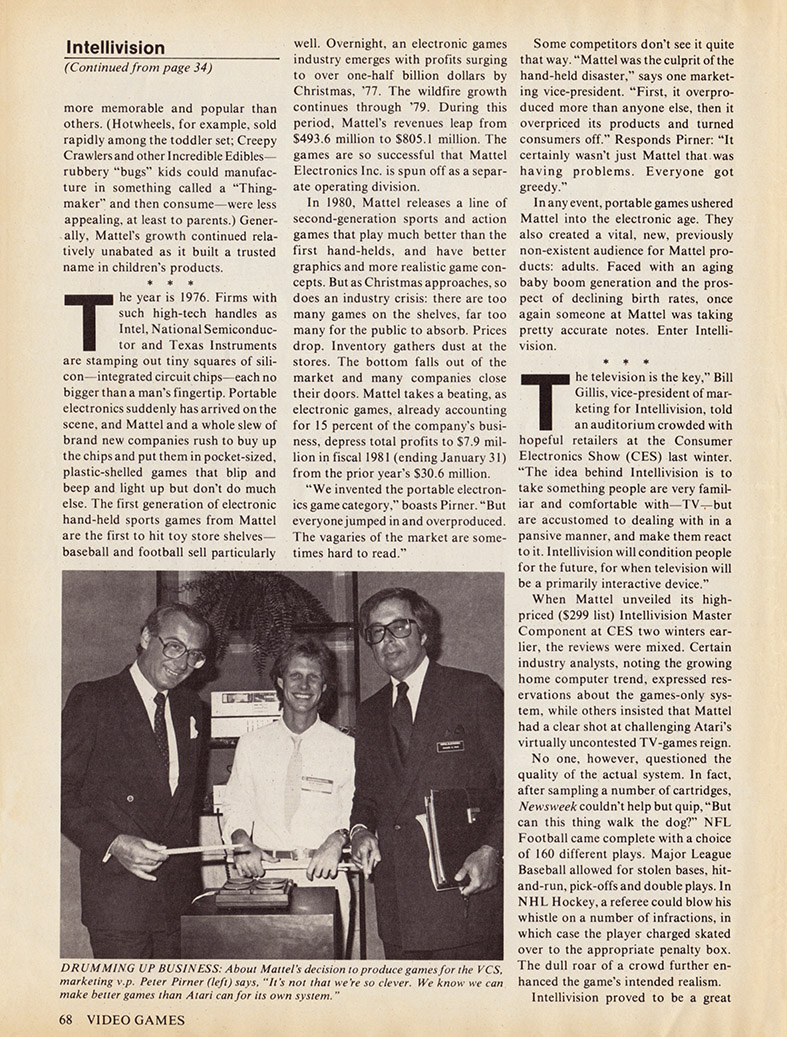

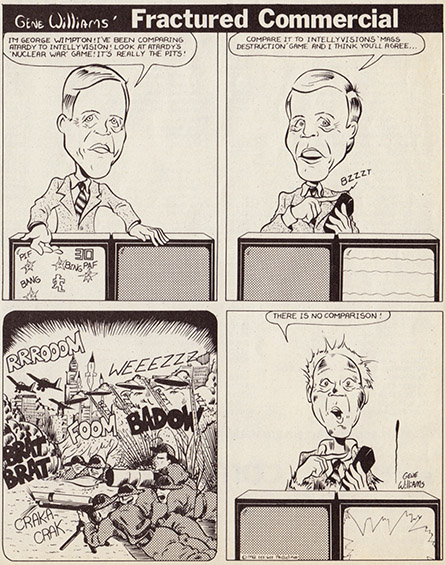

The fierce product and advertising battle lines were drawn last December and the resulting war between the two TV-game giants has become legend among videophiles. Mattel launched the first salvo with a $6 million-plus pre-Christmas television ad campaign featuring professional dilettante George Plimpton. In comparing the Atari VCS with Intellivision, Plimpton announced that the Mattel system is “more like the real thing.”

Atari counterattacked with a Poindexter-lookalike calling himself “an intelligent consumer” who simply wanted to compare Atari’s Asteroids, Missile Command and Warlords with other companies’ offerings. To his dismay, he found the others did not make those particular types of games. “Nobody compares to Atari,” Poindexter was forced to conclude.

Blip! Back to Mattel, which sallied forth with an ad featuring its own version of the Atari nerd. After the nerd mimicked Atari’s line (“When it comes to space games, nobody compares to Atari”), Plimpton suddenly appeared, informing the obviously misinformed adolescent about Intellivision’s Space Battle, Space Armada and Astrosmash games. “Gee, I didn’t know that,” the kid slobbered.

When Atari complained about this ad to all three television networks, NBC and ABC canned both companies’ spots, while CBS continued to run Mattel’s version. But that was last year. With more game companies vying for Mattel’s moderate share of the TV-game, the Madison A venue action won’t be nearly so gentlemanly this time around.

Says Pirner: “It’s World War III out there. We’re spending a lot of money [over $20 million, double the ‘81 budget]. We’re prepared to go with comparative advertising if we find it’s necessary. We’ll be hitting them (Atari) wherever their underbelly is softest.”

Does all this sound a little harsh, especially coming from the maker of Barbie dolls? “It’s a tough market,” explains Josh Denham, president of Mattel Electronics. “You’ve got to compete to stay alive and to keep your shelf space in the stores. There is a fairly narrow funnel at the retail level.”

Now a $1.13 billion a year corporation, Mattel was just a gleam in the eyes of Ruth and Elliot Handler back in 1946. The husband-and-wife team (he’s an artist) moved from Denver to southern California that year and wound up designing and manufacturing plastic doll furniture. As television began stitching itself into the fabric of American life in the ‘50s, the Handlers were busily taking notes. By 1955, Mattel—risking a substantial sum to sponsor the Mickey Mouse Club—became the first toy company to advertise on national TV.

But early products like an automatic paper cap-firing toy rifle and the musical Jack-in-the-Box were only the beginning for the Los Angeles-based firm. In 1957, Mrs. Handler noticed that her young daughter Barbara was having a good deal of fun dressing and redressing paper dolls in all the latest paper “fashions.” Accordingly, Mattel then gave birth to Barbie—the first grown-up doll with real, changeable clothing. The new “mature” look in dolls became the rage—first among young girls, then among boys as Ken strutted into toy stores. Mattel prospered.

The mid-to-late ‘60s brought a broad range of Mattel toys to market, some more memorable and popular than others. (Hotwheels, for example, sold rapidly among the toddler set; Creepy Crawlers and other Incredible Edibles—rubbery “bugs” kids could manufacture in something called a “Thing-maker” and then consume—were less appealing, at least to parents.) Generally, Mattel’s growth continued relatively unabated as it built a trusted name in children’s products.

* * *

The year is 1976. Firms with such high-tech handles as Intel, National Semiconductor and Texas Instruments are stamping out tiny squares of silicon-integrated circuit chips—each no bigger than a man’s fingertip. Portable electronics suddenly has arrived on the scene, and Mattel and a whole slew of brand new companies rush to buy up the chips and put them in pocket-sized, plastic-shelled games that blip and beep and light up but don’t do much else. The first generation of electronic hand-held sports games from Mattel are the first to hit toy store shelves—baseball and football sell particularly well. Overnight, an electronic games industry emerges with profits surging to over one-half billion dollars by Christmas, ‘77. The wildfire growth continues through ‘79. During this period, Mattel’s revenues leap from $493.6 million to $805.1 million. The games are so successful that Mattel Electronics Inc. is spun off as a separate operating division.

In 1980, Mattel releases a line of second-generation sports and action games that play much better than the first hand-helds, and have better graphics and more realistic game concepts. But as Christmas approaches, so does an industry crisis: there are too many games on the shelves, far too many for the public to absorb. Prices drop. Inventory gathers dust at the stores. The bottom falls out of the market and many companies close their doors. Mattel takes a beating, as electronic games, already accounting for 15 percent of the company’s business, depress total profits to $7 .9 million in fiscal 1981 (ending January 31) from the prior year’s $30.6 million.

“We invented the portable electronics game category,” boasts Pirner. “But everyone jumped in and overproduced. The vagaries of the market are sometimes hard to read.”

Some competitors don’t see it quite that way. “Mattel was the culprit of the hand-held disaster,” says one marketing vice-president. “First, it overproduced more than anyone else, then it overpriced its products and turned consumers off.” Responds Pirner: “It certainly wasn’t just Mattel that. was having problems. Everyone got greedy.”

In any event, portable games ushered Mattel into the electronic age. They also created a vital, new, previously non-existent audience for Mattel products: adults. Faced with an aging baby boom generation and the prospect of declining birth rates, once again someone at Mattel was taking pretty accurate notes. Enter Intellivision.

* * *

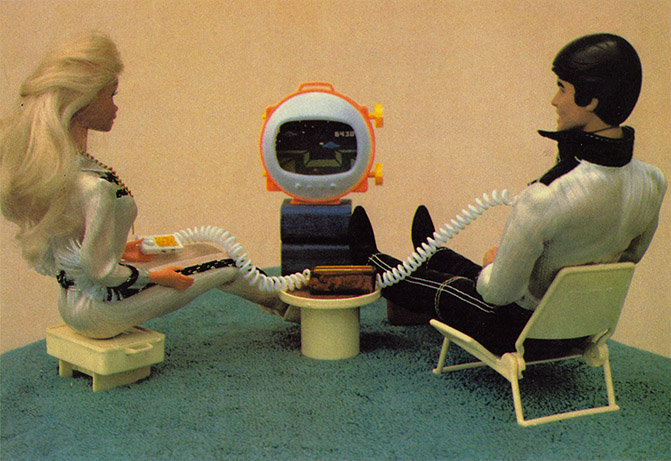

“The television is the key,” Bill Gillis, vice-president of marketing for Intellivision, told an auditorium crowded with hopeful retailers at the Consumer Electronics Show (CES) last winter. “The idea behind Intellivision is to take something people are very familiar and comfortable with—TV—but are accustomed to dealing with in a pansive manner, and make them react to it. Intellivision will condition people for the future, for when television will be a primarily interactive device.”

When Mattel unveiled its high-priced ($299 list) Intellivision Master Component at CES two winters earlier, the reviews were mixed. Certain industry analysts, noting the growing home computer trend; expressed reservations about the games-only system, while others insisted that Mattel had a clear shot at challenging Atari’s virtually uncontested TV-games reign.

No one, however, questioned the quality of the actual system. In fact, after sampling a number of cartridges, Newsweek couldn’t help but quip, “But can this thing walk the dog?” NFL Football came complete with a choice of 160 different plays. Major League Baseball allowed for stolen bases, hit-and-run, pick-offs and double plays. In NHL Hockey, a referee could blow his whistle on a number of infractions, in which case the player charged skated over to the appropriate penalty box. The dull roar of a crowd further enhanced the game’s intended realism.

Intellivision proved to be a great leap forward for TV-games: It was so effective that some found it too difficult to play. Scoring one goal in hockey, for example, might take an entire afternoon. “That’s the point,” Pirner contends. “Unlike the VCS, it takes you awhile to find out what you’ve bought.”

Nearly three years later, two-and-a-half million Intellivision owners are probably still trying to figure out what they bought. Executives at Mattel, meanwhile, must be scratching their heads, wondering what on earth it takes to command a heftier chunk of the TV-games action (only 15 percent now). One plan that temporarily quieted Mattel’s critics—mating a keyboard component with Intellivision, thus creating a formidable home computer—was only recently postponed for what seemed like the twelfth time.

Pirner concedes that “the heavy competition going on in computer hardware” hastened this latest delay. “If we had gone ahead and introduced the keyboard at the price originally intended ($500), it simply would have died in the marketplace.” A revised model should be in the stores some time in ‘83, Pirner says.

Mattel has had considerably fewer problems getting two other projects off the ground and out the door. The $100 Intellivoice (Voice Synthesis Module), which talks to you when plugged into Intellivision and used with specially made cartridges, will be available this Christmas. So too will a new series of cartridges going under the heading “M Network.” But don’t try to play them on your Intellivision; these games are stamped Atari VCS only.

Isn’t it ironic that Mattel has begun to produce software for its closest rival’s hardware—even though 75 percent of TV-games users own the VCS? Peter Pirner doesn’t think so. “Although we’re in second place, we know we can make better games for the number one company than Atari can for its own system,” he brags. “It’s not that we’re so clever. We just see the market need, like Activision and all those other cartridge companies have done, and decided to address it.

“Some people have said that we’re admitting defeat to Atari by doing this. That’s ridiculous. Activision, Imagic and Coleco are all starting to ship cartridges for Intellivision. I don’t know about you, but I take that as a vote of confidence for Mattel, not a sign of defeat.”

Three hundred miles north, up in California’s reknowned Silicon Valley, the Atari camp remains smug. “Every time they advertise cartridges for our system,” chides an executive, “they’ll be contradicting their own ad.”

And so the battle goes on. Despite Intellivision’s enormous impact in the TV-games field, Mattel’s goal to catch Atari may never be realized. But don’t tell that to Mattel. Just as this article hit the press, the company announced a month-long $50 rebate program for Intellivision. For the first time, you could buy the system for under $200.

And Plimpton (remember him?) was busy rehearsing the script for Mattel’s next prime-time dig at Atari—an ad for Intellivoice. Get this line: “Now you can tell the difference between Intellivision and Atari with your eyes closed.” Touché!

Nobody Compares to George Plimpton

Long before author and now actor (Reds) George Plimpton began pitching Mattel’s Intellivision on prime time, he had built a reputation as the Walter Mitty of sports, living out every man’s fantasy to be a professional athlete at least for one day. In Paper Lion (which was made into a movie starring Alan Alda as Plimpton), Plimpton observed the world of football while trying to make it as a quarterback with the Detroit Lions. (He played five downs in an intra-squad scrimmage, fumbling twice, falling down once, running once for no gain and throwing an incomplete pass.) His subsequent experiments, including a five-minute exhibition stint as a hockey goalie and a crack at stand-up comedy at Caesar’s Palace, were detailed at length in books and magazines like Sports Illustrated and Playboy. Just how did George Plimpton come to be the Karl Malden of the TV-game ad war? VIDEO GAMES asked fellow writer and sportsman Stephen Hanks to find out. Hanks caught up with Plimpton at his summer home in the Hamptons where he was partying and working on his next non-fiction book, titled Fireworks.

VIDEO GAMES: Certainly, Mattel could have selected a “real” athlete to be its television spokesperson—say, Reggie Jackson, Tug McGraw or Mean Joe Greene—but they picked you. Why was that?

PLIMPTON: I guess it was because of my image as the ultimate participant. I’ve tried playing a lot of sports on a professional level, and I’ve achieved a certain amount of credibility as someone who’s always in pursuit of excellence. Mattel probably felt people would believe me when I explained the differences between Mattel and Atari games.

VG: Were you familiar with the games at the time?

PLIMPTON: Not really. But there’s such a thing as truth in advertising, so I had to play a lot of Mattel and Atari games before I could go on the air.

VG: Then you really do prefer Intellivision?

PLIMPTON: Definitely. If I hadn’t found the Mattel games better, I wouldn’t have done the commercials. I really believe very strongly that Mattel’s games—especially the sports games—are superior to Atari’s.

VG: How do you account for the tremendous success and popularity of video games?

PLIMPTON: They’re just great fun! I think their 21st century, three-dimensional look and feel is extremely attractive to people. I have to admit that I’m in awe of the imaginative people who invent and engineer these games.

VG: How long do you think the craze will last?

PLIMPTON: I definitely don’t think it’s a craze. Any game that is entertaining will last in some form or another, whether it be Pac-Man, Space Invaders, Parcheesi or Monopoly.

VG: Speaking of Pac-Man, do you play it often?

PLIMPTON: Well, I must admit, I really don’t play any of the games much and I haven’t played Pac-Man at all.

VG: I would think you’d almost have to avoid Pac-Man to have not played it.

PLIMPTON: Well, anytime I pass an arcade and want to play it, there’s always someone ahead of me at the machine. But Hugh Hefner has a big gameroom at the Playboy Mansion, and if there’s a Pac-Man machine free the next time I’m there, I’ll play it. Besides, at Hef’s you don’t have to put any quarters in.

VG: You must find the time to play Intellivision, though.

PLIMPTON: Beyond experimenting with the games Mattel is currently advertising, no. I just don’t play. It’s too time-consuming.

VG: Have you read any of the video game books?

PLIMPTON: None. That would be more of a time-waster than playing the games.

VG: Some people feel video games are bad for children, that kids are playing the games too much. What do you think?

PLIMPTON: Although I find the sights and sounds of arcades fascinating, I don’t go to the arcade parlors, and I’d be very upset if my kids spent a lot of time around them. Parents have to be on guard to prevent over-indulgence, but ultimately I don’t feel the games really harm children in any way.

VG: Is there a specific kind of new game you would like to see invented?

PLIMPTON: Yes. I’d like to see games where kids can actually learn useful things while playing them at home. Games could teach you how to ski or how to speak Russian or Chinese or how to fly an airplane or drive a car. The teaching aspect is vastly under-developed, but I think we’ll start seeing things like this in the next five years.

VG: Last question. Since you’ve tried your hand at almost every major sport, how do you feel about competing against a video game champion?

PLIMPTON: That’s an interesting thought. I just don’t know if I could handle it. You have to have. a considerable bladder to stand and play these games as long as some of these kids do. That would be very tough.

Source Pages