Computer Gaming

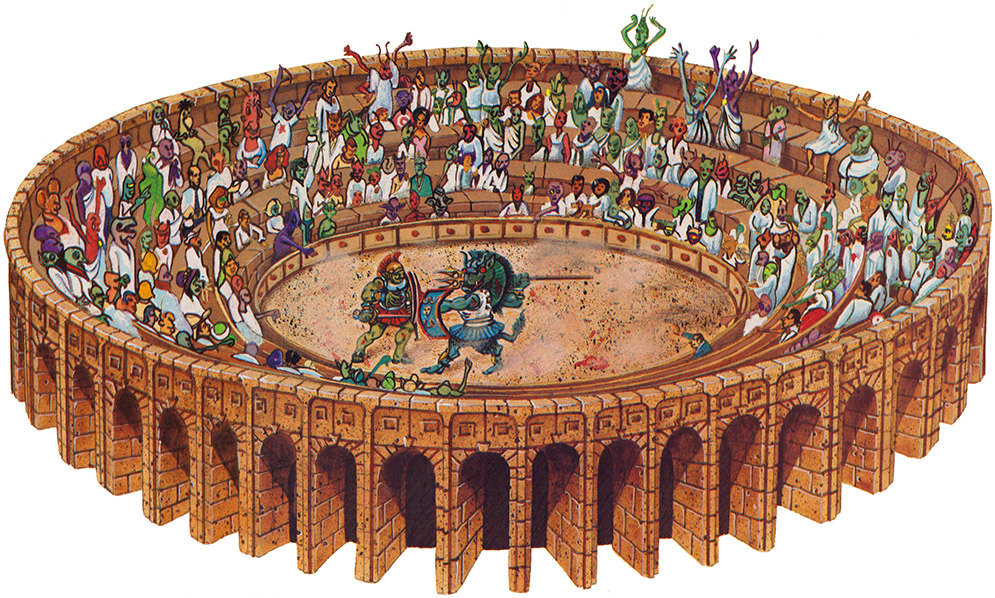

Can Your Combat Team Survive Galactic Gladiator’s Deadly Arena?

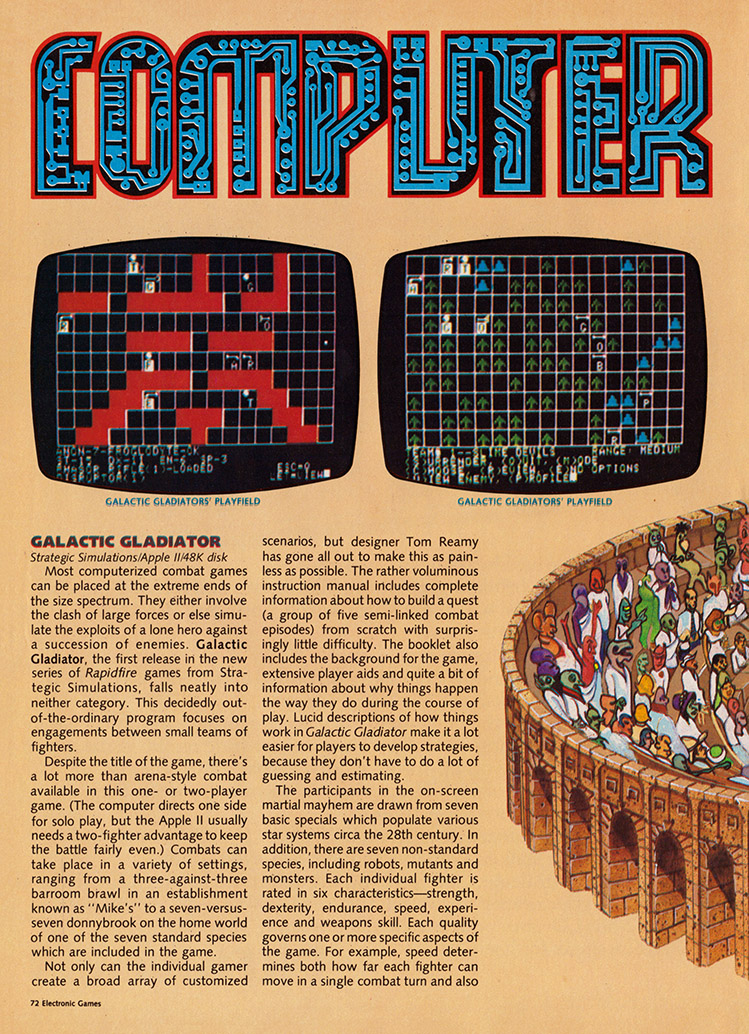

GALACTIC GLADIATOR

Strategic Simulations/Apple II/48K disk

Most computerized combat games can be placed at the extreme ends of the size spectrum. They either involve the clash of large forces or else simulate the exploits of a lone hero against a succession of enemies. Galactic Gladiator, the first release in the new series of Rapidfire games from Strategic Simulations, falls neatly into neither category. This decidedly out-of-the-ordinary program focuses on engagements between small teams of fighters.

Despite the title of the game, there’s a lot more than arena-style combat available in this one- or two-player game. (The computer directs one side for solo play, but the Apple II usually needs a two-fighter advantage to keep the battle fairly even.) Combats can take place in a variety of settings, ranging from a three-against-three barroom brawl in an establishment known as “Mike’s” to a seven-versus-seven donnybrook on the home world of one of the seven standard species which are included in the game. Not only can the individual gamer create a broad array of customized scenarios, but designer Tom Reamy has gone all out to make this as painless as possible. The rather voluminous instruction manual includes complete information about how to build a quest (a group of five semi-linked combat episodes) from scratch with surprisingly little difficulty. The booklet also includes the background for the game, extensive player aids and quite a bit of information about why things happen the way they do during the course of play. Lucid descriptions of how things work in Galactic Gladiator make it a lot easier for players to develop strategies, because they don’t have to do a lot of guessing and estimating.

The participants in the on-screen martial mayhem are drawn from seven basic specials which populate various star systems circa the 28th century. In addition, there are seven non-standard species, Including robots, mutants arid monsters. Each individual fighter is rated in six characteristics—strength, dexterity, endurance, speed, experience and weapons skill. Each quality governs one or more specific aspects of the game. For example, speed determines both how far each fighter can move in a single combat turn and also indicates which will get to move first. Strength, on the other hand, determines what kind of arms and armor a battler can carry into the fray as well as how much damage it takes to kill or stun that fighter.

Variety is the hallmark of Galactic Gladiator. Even before getting into the design-it-yourself options, there is an amazing flexibility that is guaranteed to keep this program from going stale the first week out of its box. And by the time truly dedicated fans of Galactic Gladiator have explored most of the nuances of the original game, Reamy plans to have a data disk available that will add a raft of new possibilities to Investigate.

Galactic Gladiator has all the elements of a potential cult classic. It gives gamers so much input into the design of scenarios while keeping actual play smooth and simple, leaving players free to exercise their brain cells on concocting all kinds of weird, deadly strategies.

(Arnie Katz)

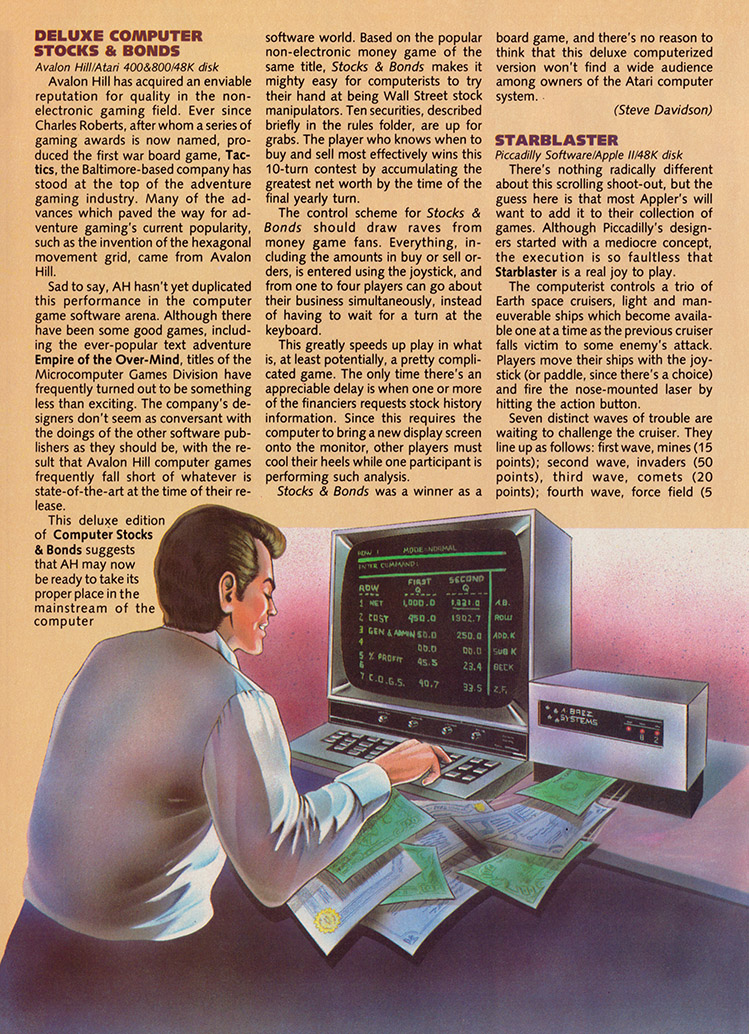

DELUXE COMPUTER STOCKS & BONDS

Avalon Hill/Atari 400&800/48K disk

Avalon Hill has acquired an enviable reputation for quality in the non-electronic gaming field. Ever since Charles Roberts, after whom a series of gaming awards is now named, produced the first war board game, Tactics, the Baltimore-based company has stood at the top of the adventure gaming industry. Many of the advances which paved the way for adventure gaming’s current popularity, such as the invention of the hexagonal movement grid, came from Avalon Hill.

Sad to say, AH hasn’t yet duplicated this performance in the computer game software arena. Although there have been some good games, including the ever-popular text adventure Empire of the Over-Mind, titles of the Microcomputer Games Division have frequently turned out to be something less than exciting. The company’s designers don’t seem as conversant with the doings of the other software publishers as they should be, with the result that Avalon Hill computer games frequently fall short of whatever is state-of-the-art at the time of their release.

This deluxe edition of Computer Stocks & Bonds suggests that AH may now be ready to take its proper place in the mainstream of the computer software world. Based on the popular non-electronic money game of the same title, Stocks & Bonds makes it mighty easy for computerists to try their hand at being Wall Street stock manipulators. Ten securities, described briefly in the rules folder, are up for grabs. The player who knows when to buy and sell most effectively wins this 10-turn contest by accumulating the greatest net worth by the time of the final yearly turn.

The control scheme for Stocks & Bonds should draw raves from money game fans. Everything, including the amounts in buy or sell orders, is entered using the joystick, and from one to four players can go about their business simultaneously, instead of having to wait for a turn at the keyboard.

This greatly speeds up play in what is, at least potentially, a pretty complicated game. The only time there’s an appreciable delay is when one or more of the financiers requests stock history information. Since this requires the computer to bring a new display screen onto the monitor, other players must cool their heels while one participant is performing such analysis.

Stocks & Bonds was a winner as a board game, and there’s no reason to think that this deluxe computerized version won’t find a wide audience among owners of the Atari computer system.

(Steve Davidson)

STARBLASTER

Piccadilly Software/Apple II/48K disk

There’s nothing radically different about this scrolling shoot-out, but the guess here is that most Appler’s will want to add it to their collection of games. Although Piccadilly’s designers started with a mediocre concept, the execution is so faultless that Starblaster is a real joy to play.

The computerist controls a trio of Earth space cruisers, light and maneuverable ships which become available one at a time as the previous cruiser falls victim to some enemy’s attack. Players move their ships with the joystick (or paddle, since there’s a choice) and fire the nose-mounted laser by hitting the action button.

Seven distinct waves of trouble are waiting to challenge the cruiser. They line up as follows: first wave, mines (15 points); second wave, invaders (50 points), third wave, comets (20 points); fourth wave, force field (5 points); fifth wave, guardians, (55-85 points depending on the skill level); sixth wave, space rocks (50-75 points) and seventh wave, neutron bombs (25-75 points) and the Dragonian Annihilator (5,000-12,500 points). Bursting through the Annihilators defensive wall and blasting it to smithereens earns gamers the right to run through the whole obstacle course again at a higher level of difficulty. Starblaster has eight levels, each a bit faster or more complex than the last.

One often-heard complaint about scrolling shoot-outs is that only the good scorers ever get to see all the screens, while a player who’s having a tougher time of it may spend 50 games trying to break out of the first scenario. Starblaster addresses this issue by providing a demonstration mode, which can be chosen by pressing the “D” key after the program boots. The demo can be an exhilarating experience for arcaders who ordinarily get trounced by Tron and zapped by Zaxxon. You can move and fire, but no amount of damage will cause you to lose a ship. To keep this sudden invincibility from overwhelming players, no points are recorded on the tote board.

The graphics in Starblaster rate as serviceable, but not spectacular. The design emphasizes clean linework and straightforward rendering rather than eyeball-searing pyrotechnics. Yet the on-screen images are well-drawn enough to escape the clunky look that sometimes mars cartridges in the videogame field. Sound effects aren’t great, but that’s as much the fault of the Apple as the programmer.

If you’re looking for a good multi-scenario space game, Starblaster is a good bet.

(Steve Davidson)

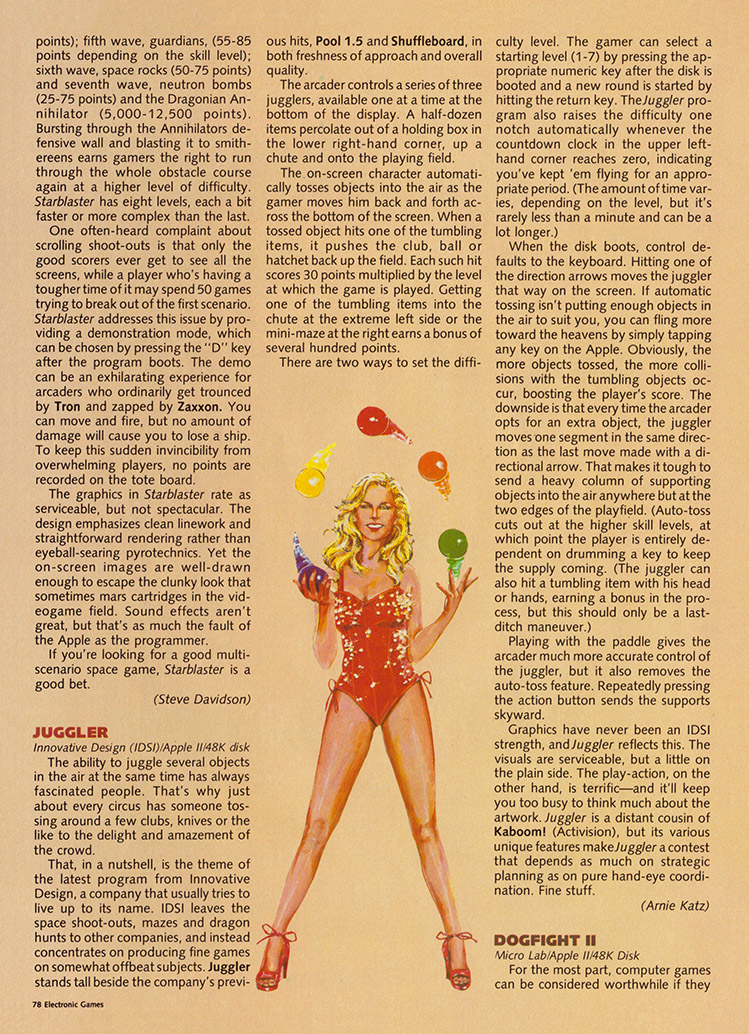

JUGGLER

Innovative Design (IDSI)/Apple II/48K disk

The ability to juggle several objects in the air at the same time has always fascinated people. That’s why just about every circus has someone tossing around a few clubs, knives or the like to the delight and amazement of the crowd.

That, in a nutshell, is the theme of the latest program from Innovative Design, a company that usually tries to live up to its name. IDSI leaves the space shoot-outs, mazes and dragon hunts to other companies, and instead concentrates on producing fine games on somewhat offbeat subjects. Juggler stands tall beside the company’s previous hits, Pool 1.5 and Shuffleboard, in both freshness of approach and overall quality.

The arcader controls a series of three jugglers, available one at a time at the bottom of the display. A half-dozen items percolate out of a holding box in the lower right-hand corner, up a chute and onto the playing field.

The on-screen character automatically tosses objects into the air as the gamer moves him back and forth across the bottom of the screen. When a tossed object hits one of the tumbling items, it pushes the club, ball or hatchet back up the field. Each such hit scores 30 points multiplied by the level at which the game is played. Getting one of the tumbling items into the chute at the extreme left side or the mini-maze at the right earns a bonus of several hundred points.

There are two ways to set the difficulty level. The gamer can select a starting level (1-7) by pressing the appropriate numeric key after the disk is booted and a new round is started by hitting the return key. The Juggler program also raises the difficulty one notch automatically whenever the countdown clock in the upper left-hand corner reaches zero, indicating you’ve kept ‘em flying for an appropriate period. (The amount of time varies, depending on the level, but it’s rarely less than a minute and can be a lot longer.)

When the disk boots, control defaults to the keyboard. Hitting one of the direction arrows moves the juggler that way on the screen. If automatic tossing isn’t putting enough objects in the air to suit you, you can fling more toward the heavens by simply tapping any key on the Apple. Obviously, the more objects tossed, the more collisions with the tumbling objects occur, boosting the player’s score. The downside is that every time the arcader opts for an extra object, the juggler moves one segment in the same direction as the last move made with a directional arrow. That makes it tough to send a heavy column of supporting objects into the air anywhere but at the two edges of the playfield. (Auto-toss cuts out at the higher skill levels, at which point the player is entirely dependent on drumming a key to keep the supply coming. (The juggler can also hit a tumbling item with his head or hands, earning a bonus in the process, but this should only be a last-ditch maneuver.)

Playing with the paddle gives the arcader much more accurate control of the juggler, but it also removes the auto-toss feature. Repeatedly pressing the action button sends the supports skyward.

Graphics have never been an IDSI strength, and Juggler reflects this. The visuals are serviceable, but a little on the plain side. The play-action, on the other hand, is terrific—and it’ll keep you too busy to think much about the artwork. Juggler is a distant cousin of Kaboom! (Activision), but its various unique features make Juggler a contest that depends as much on strategic planning as on pure hand-eye coordination. Fine stuff.

(Arnie Katz)

DOGFIGHT II

Micro Lab/Apple II/48K Disk

For the most part, computer games can be considered worthwhile if they do something better than can be done in any other format, or if they offer an entirely new idea. Dogfight II, unfortunately, falls a bit short of doing either.

Most home videogame systems include some type of plane-battle game. The characteristics of the planes may differ and the controls might be of differing formats, but the premise is the same.

Dogfight II is different from those games in only a couple of ways. First, there is the option of playing against a human or computer opponent. Then there is a pilot. He often bails out after his plane gets shot down and must be blasted out of the sky, lest he somehow gets back into his plane and live to fight again. The program also throws in a helicopter.

Many of the game’s features involve the different mode-of-operation options. The game can be played with keyboard, one joystick, two joysticks or paddles. When playing against the computer, one player can provide opposition, two players can fight on the same team against the computer or both can battle each other and the computer. Then there is the custom mode where the gamer can pick jets or helicopters, the speed of the game and determine the teams.

When using the keyboard, up to eight players can compete at once, if you can figure out how to get eight full-size bodies behind the same keyboard. In the keyboard version, the movement of the planes is the least satisfactory. For the first player, letter “Z” makes the plane bank left, “C” banks the plane right, “S” slows the plane down and “D” speeds it up. Letter “X” fires the gun. Using a key to bank in one direction is fine, but making the gamer use the opposite bank key to come out of the bank and then hit it again to bank in the opposite direction takes a lot of practice and makes for sluggish play.

When employing the paddle mode, you merely turn the knob in the direction you want the plane to fly and press the button to fire. You still must use the keyboard to increase or decrease speed. Joystick is the most effective. Pushing the joystick forward increases the speed, pulling back slows it down, pulling to the left banks the plane in that direction and pulling to the right banks it right. The button fires the gun. When a gamer’s plane is hit, he must hit the button right away to bail out of the craft and have a chance to fight again.

Players get 10 points for each plane and for each pilot shot down. If the computer bails the pilot out without a chute he falls very rapidly and is worth 50 points when hit. (If he bails out without a chute he won’t return to his plane, regardless of whether he is it.) Rarely, he appears in a capsule. In that event, he’s worth 100 points when hit.

For pilots who survive a round, the computer awards 10 bonus points for each plane that started the round against you. The display shows how many planes you have left (you begin with five), the point total, play level and the high score in the current mode since the computer was turned on. High scores from previous sessions aren’t saved. An extra jet is awarded for each 1,000 points. The gun holds four bullets, which are reloaded at a rate of one per second. An itchy trigger finger can make the gun inoperable for a short time.

Overall, one would expect more graphics and more detail with a computer game that uses so much memory.

(Rick Teverbaugh)

MOONBASE IO

PDI/Atari 400 & 800/16K cassette, 32K disc (with cassette)

You have awakened from a deep sleep,” a voice intones at the beginning of Moonbase Io. On the playfield there is a portal looking out into deep space. A computer guidance console lines the wall of your ship, the Juno 9.

PDI, the software producer responsible for Moonbase Io, has done more for the “talking videogame” than anyone else in the field. Without sophisticated speech-synthesis chips or any other high-tech wizardry, PDI has consistently experimented with the integration of spoken word and videogame action in their Atari computer software. The designers’ only tool has been the Atari 410, the specially-modified tape recorder used to load programs on audio-cassette format.

Moonbase Io further evolves the use of audiotape in game-playing—even the disc version comes with a cassette! The arcader is the pilot, playing a series of machine-language arcade contests in order to secure the three moons and their transmitters.

Phase one involves blasting through a field of space deathtraps with limited energy and firepower. The ship must then be steered in orbit around the satellite and docked for refueling. A multi-staged high-quality invader game follows before the Juno 9 can cross the plains of the final moon.

After each successful phase—losers must go back to square one-hearty congratulations are relayed from a chattering control room back on Earth. The final command is then issued: go in after the mothership itself. Fragmentary reports from the few previous pilots who got this far reported that the big ship was protected by “breakout shields” which must be blown up one layer at a time.

Should you actually wipe out the mothership you will hear the screams on board the doomed craft, followed by a personal congrats from the Federation President!

Moonbase Io has to be seen—and heard—to be believed. First rate production values are of the highest calibre almost everywhere—if only their packaging were a bit sturdier…

(Bill Kunkel)

Source Pages