Behind the Scenes

Tragic Imagic

It has all the elements of a classical tragedy: a collection of good-natured, creative people of integrity rise to the heights of artistic and financial success, only to be ruined by their own tragic flaws or the machinations of fate.

Dramatic, isn’t it? Not completely true, however. Imagic is not ruined, not yet.

In October, spokesman Margaret Davis announced that Imagic had been forced to lay off most of its work force. It was revealed that, henceforth, Imagic would be solely a game design house; they would discontinue production of their own games. Industry insiders feel that lmagic is very close to total extinction.

How could a company which has consistently produced games with innovative graphics and gameplay, games that were attractively packaged and well promoted—how could such a company fall so far, so fast?

Imagic’s tragic flaw appears to be mismanagement, an inability or unwillingness to cope with high finance, which led to a disastrous decision late last year. Fate intervened in the forms of a sudden, industry-wide turnaround in software sales and the appearance of an outer space Grinch that stole their Christmas: E.T.

CHRISTMAS CLIMB

In 1981, there was such a shortage of new videogame cartridges for the Atari 2600 that, it seemed, any new game automatically became a bestseller. Each of these games only cost four dollars to manufacture, and they were retailing for around thirty dollars. With such huge sums to be made, dozens of companies scrambled to get their share.

By Christmastime, the shortage of 1981 was but a memory.

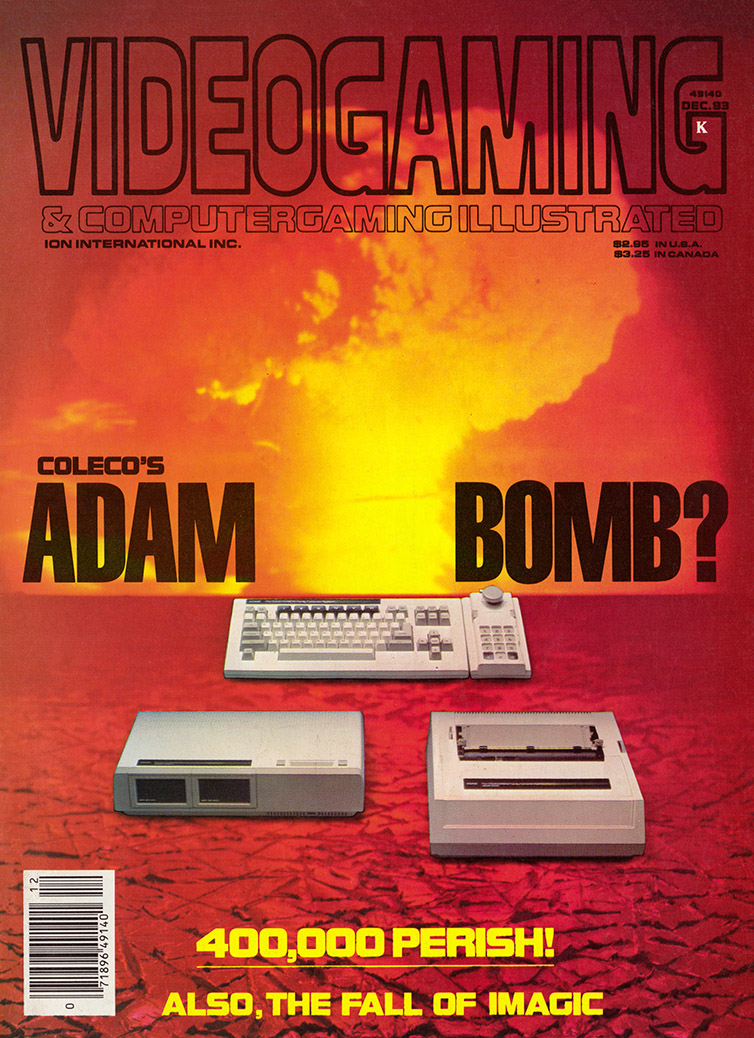

Although many of the new companies—CBS Electronics, Fox Games of the Century, Parker Brothers, Coleco—were subdivisions of larger companies with “deep pockets” (considerable financial backing), most were smaller, hastily assembled companies.

Through Christmas 1981 and the first six months of 1982, the Golden Age of the 2600 was upon us, and the times of shortage and drought were but a memory. Cartridge sales were phenomenal.

The Golden Age was not to last, however. With a glut of new cartridges, shelf space on the retail level became scarce. Many of the companies could not find distribution. Also, the introduction of Intellivision and, especially, ColecoVision and the Atari 5200 stole the glow from the humble 2600. While those companies with large financial backing had the resources to adapt, many of the smaller ones did not and faded from view.

One exception to the smaller company rule was Imagic. In March 1982, Imagic released its first three games, Trick Shot, Star Voyager, and Demon Attack. Demon Attack quickly shot to the top of the bestseller lists and stayed there. Demon Attack money helped Imagic adapt to the changing market… for a while.

In its first year, Imagic released twenty-five cartridges in all, including adaptations of their 2600 games to Intellivision. This was far more titles than any other game company, including Atari and Activision. Imagic reportedly sold over $75 million worth of cartridges, $10 million more than that sold by Activision during the same period (Activision released seven fewer games than Imagic). Despite the superior sales, Imagic could not shake Activision from its first place slot. And this flood of activity was laying the groundwork for their demise as a game production company.

INTERMISSION

At this time it is important to note some random but relevant points of information.

Imagic was founded by four game designers. Activision was founded by four game designers and a former record company executive whose major strength was in marketing (James Levy). Since the game cartridge retail business is in many ways similar to the record retail business, Levy’s expertise would eventually see Activision through the dark times to come. As will soon become apparent, Imagic’s talented game designers were either unlucky or ill-equipped to deal with those same dark times. Most businessmen will tell you there’s no such thing as luck.

Frank Mainero, marketing V.P. for Activision, maintains that companies who panic and stray from long-term strategic plans will be the ones that file for Chapter 11. Since its inception, Activision has taken one step at a time in its game development and marketing. The company didn’t begin developing Intellivision-compatible cartridges until almost two years after the system appeared. Likewise, three years after the first Activision cartridges were released, the company is just now releasing games for computers (two of their mega-hits, River Raid and Kaboom!).

Imagic, on the other hand, seems given to impulse decisions. When the company was first founded, it was announced that Imagic would produce games for Intellivision. It was not until nearly six months later that Intellivision-compatible Demon Attack and Atlantis appeared. Likewise, in January of this year (when the writing was already on the wall), Imagic announced that they would be designing games for Odyssey, Commodore and the Atari computers in addition to the previously mentioned units. Moreover, Imagic signed an exclusive contract with Texas Instruments to develop games for their home computer, and mere weeks later, TI stock tumbled 41½ points in one point week and the company reported losses for the quarter in the millions. Bad luck for Imagic? Perhaps, but hard-noses who don’t believe in luck might well term it “poor research, poor planning…panic.”

Now let’s examine the events surrounding Christmas 1982, a disastrous season for the software business in general, and Imagic in particular.

CHRISTMAS CRASH

The following account has been deduced from facts and information special to VCI.

During the third and fourth quarters of 1982, the powers-that-be at Imagic decided that they wanted to make a public offering of their stock. When a public stock offering is made, a group of underwriters (brokers such as Merrill Lynch or others) will buy all of a given company’s stock at a price slightly lower than it will be offered to the public. In this way, the company gets all of its money at one time and the underwriters will make their profit once they in turn sell the stock to the public.

The first step in making a public offering of stock is for the company to file a registration statement with the Securities and Exchange Commission; this statement contains the company’s prospectus. For a period. of four to six weeks the SEC reviews the company’s statement to be sure they have complied with all points of the law.

This period of review is a very sensitive time. If, during this time, something happens that would substantially change the information in the statement, the statement becomes invalid and amendments must be filed. The new information could be good news or bad news.

If the news is so bad that the company (and the brokers) don’t feel that the stock will sell at the price designated, then the statement may be pulled or the matter may be dropped. In any case, it is a profound embarrassment to both company and brokerage firm.

It appears that this last situation applies to Imagic.

Blame it on E.T. and disastrous timing on the part of Imagic.

Just prior to, or during, the period of Imagic’s review, Atari’s stock plummeted in the wake of an announcement of hundreds of millions of dollars in lost revenues; Apollo, another game company, went under; and the situation that had been developing on the retail level blew up.

The name of the game is shelf space; that game has been played for years. The name of the game is “who will bear the risk of carrying all these dang cartridges?”; that game is relatively new. It is played like this:

You’re Sven, owner of Sven’s Video Madness. In May, you buy a hundred Microsurgeons from Imagic. They’re yours now, Sven. You can’t return them to Imagic. They don’t sell so good. In July, you buy a hundred Firefighters from Imagic—all yours. No return. They don’t sell so hot, either. In November, Imagic offers you three or four games. They look good, nice packages. But you just bought a million copies of E.T. from Atari and you don’t have the space to display the Imagic cartridges. Imagic games haven’t been selling that well, anyway, so you tell Imagic to take a walk. Lo and behold, Sven. E.T. doesn’t sell either. Your stockroom is full with Microsurgeons and E.T.s…and, because you bought them all, no return (lots of money spent, none coming in), you’re out of business, my man.

After the Christmas of 1982, when E.T. pushed a lot of other games off the shelves (many E.T. games were sold, by the way, it’s just that Atari pressed millions and millions of them) and it didn’t sell proportionately, the Svens of the nation demanded a new inventory policy with the gamesmakers: they would make smaller and fewer purchases of the games, and the software companies would have to bear a measure of the risk.

There is evidence to suggest that, during this time, Imagic agreed to buy millions of their old games back in order to obtain shelf space for their new games. Shortly following, Imagic had to sell $12 million worth of its privately held stock in order to raise the revenues to pay the storage fees on its old cartridges. And so on and so on. Bad news has its own momentum.

Imagic is not out of the picture yet. Their games will be offered on the Gameline system. Imagic continues to survive (and, we hope, thrive) as a game design firm. But many jobs—many opportunities—have been lost.

Activision has succeeded, not only because they have released hit after hit, but because they have carefully planned their every move and stuck to that plan. But if you are looking for a lesson in the fall of Imagic, a comparison with Activision is not valid. Tell an American entrepreneur that (s)he should not act out of instinct or aggressiveness and that entrepreneur will laugh in your face.

No, if lesson there be, it is a bitter one for artists of all disciplines, a lesson that true artists might be wise to ignore: in this day and age, it is not enough to be creative, to be brilliant, and to work hard. If success is the goal, if communication is the goal, the art must be sold, packaged, marketed and displayed—and a cold eye must be kept on competitors.

Otherwise, art becomes inventory.

Source Pages